Emerging science tells us an optimistic story about the potential of all learners. There is burgeoning knowledge about the biological systems that govern development, including deeper understandings of brain structure and wiring and their connections to other systems and the external world. This research tells us that brain development and life experiences are interdependent and malleable— that is, the settings and conditions individuals are exposed to and immersed in affect how they grow throughout their lives.

This knowledge about the brain and development, coupled with a growing knowledge base from educational research, provide us with an opportunity to design systems in which all individuals are able to take advantage of high-quality opportunities for transformative learning and development. The situation facing our country today—sharp and growing economic inequality, ongoing racial violence, the physical and psychological toll of the pandemic—underscores our need to enable societal and educational transformations that advance social justice and the opportunity to thrive for each and every young person.

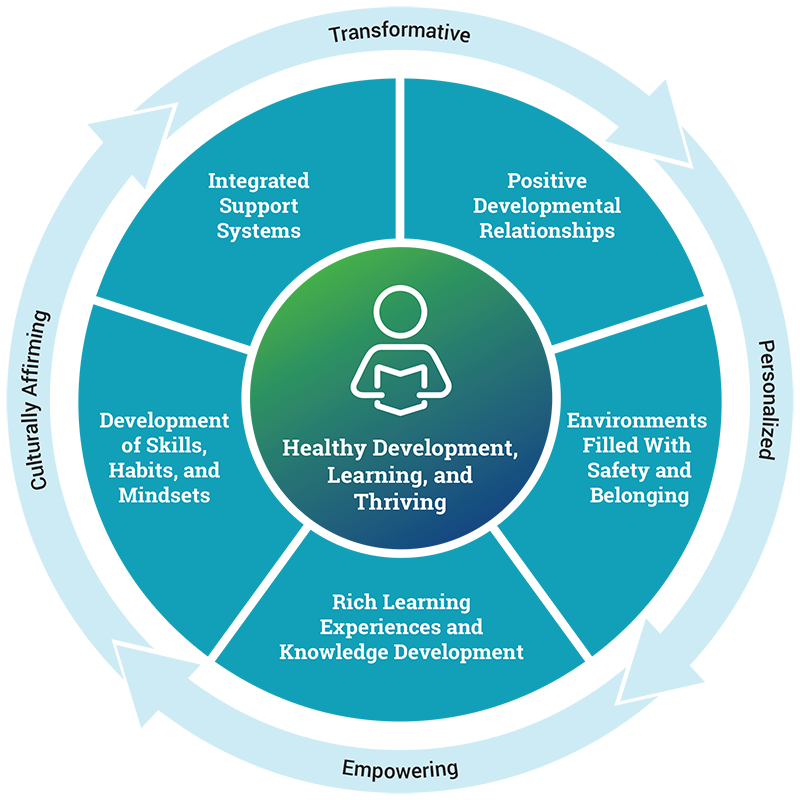

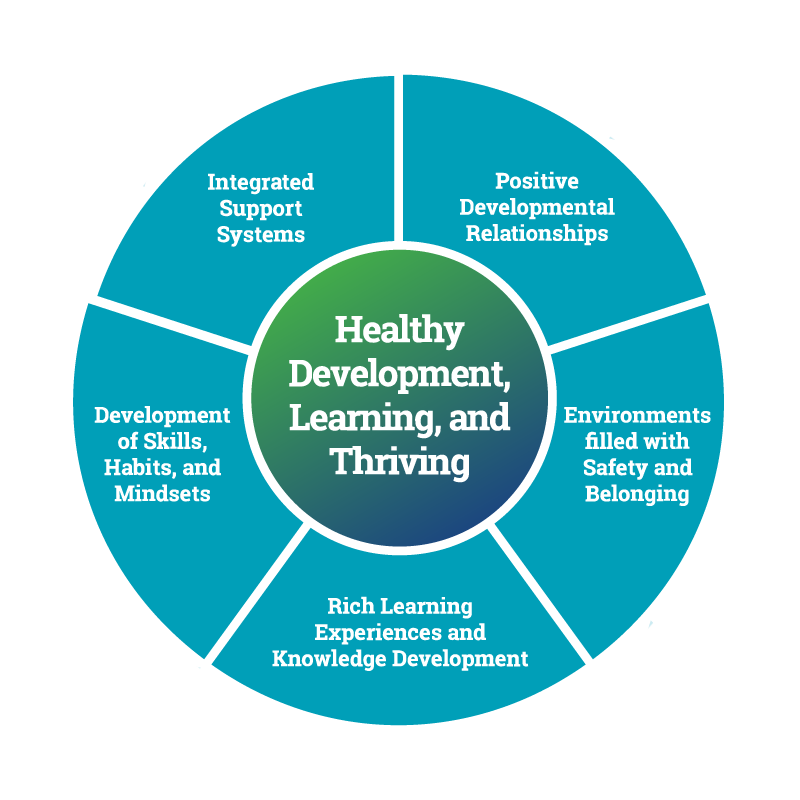

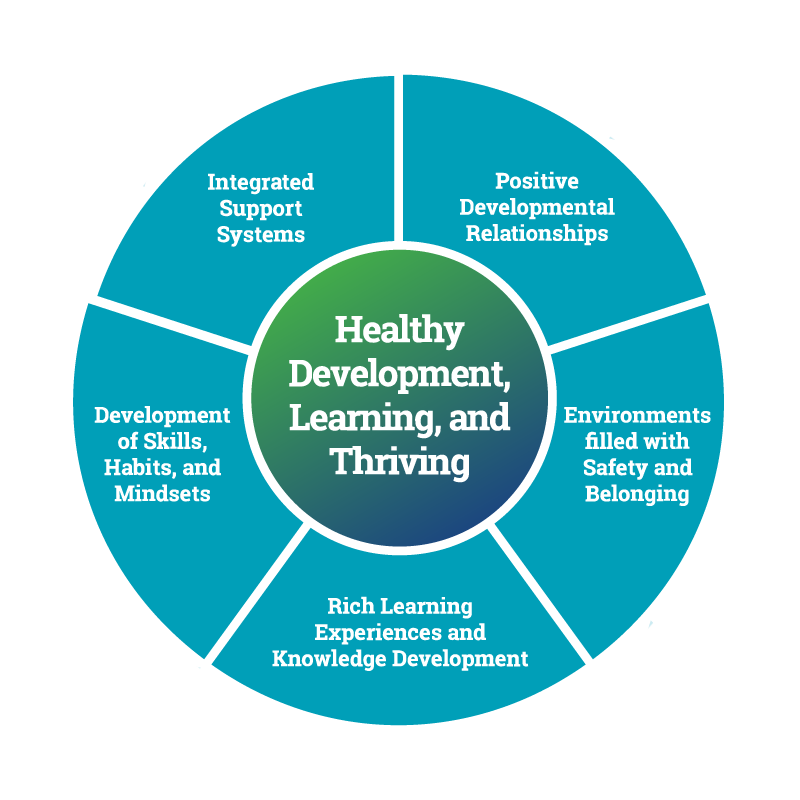

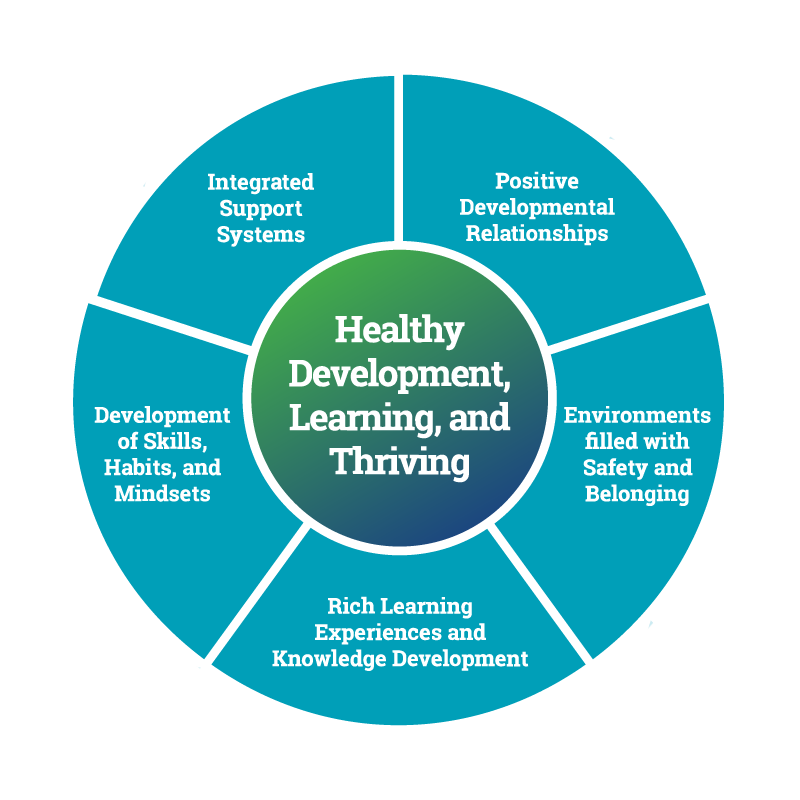

The Guiding Principles for Equitable Whole Child Design aims to seize this opportunity to advance change. The organizing framework to guide transformation of learning settings for children and adolescents is reflected in the five elements shown in Figure 1.1:

|

Figure 1.1 Guiding Principles for Equitable Whole Child Design

|

|

Although these elements resonate with most educators, they have not yet been widely used to develop and create learning settings, nor have they been engineered in fully integrated ways to yield healthy development, learning, and thriving. Progress has been impeded by both historical traditions and current policy built on dated assumptions about school design, accountability, assessment, and educator development. Current constraints do not support robust implementation, let alone integration of these practices. If, however, the purpose of education is the equitable, holistic development of each student, scientific knowledge from diverse fields can be used to redesign policies and practices to create settings that unleash the potential in each student.

Redesign around these core principles has implications for all levels of the ecosystem, from the classroom to the school, district, and larger macrosystems that must join together to produce an intentionally integrated, comprehensive developmental enterprise committed to equity for all students, not just some. We separate and enumerate each component individually, but we believe the unique application of these components will be to use them in reinforcing and integrated ways to truly support learner needs, interest, talents, voice, and agency. The aim is a context for development that is greater than the sum of its parts and is transformative, personalized, empowering, and culturally affirming for each student.

Below is a brief description of this organizing framework, in which we describe how each of the Guiding Principles for Equitable Whole Child Design is associated with research from developmental and learning science. We also briefly describe how each element is associated with:

That relationships are important is not new knowledge to educators, families, or researchers. Relationships engage children in ways that help them define who they are, what they can become, and how and why they are important to other people. However, not all relationships are developmentally supportive. In a developmental relationship, caring and attachment are joined with adult guidance that enables children to learn skills, grow in their competence and confidence, and become more able to perform tasks on their own and take on new challenges. Children increasingly use their own agency to develop their curiosity and capacities for self-direction. Looked at this way, developmental relationships can both buffer the impact of stress and provide a pathway to motivation, self-efficacy, learning, and further growth.

That relationships are important is not new knowledge to educators, families, or researchers. Relationships engage children in ways that help them define who they are, what they can become, and how and why they are important to other people. However, not all relationships are developmentally supportive. In a developmental relationship, caring and attachment are joined with adult guidance that enables children to learn skills, grow in their competence and confidence, and become more able to perform tasks on their own and take on new challenges. Children increasingly use their own agency to develop their curiosity and capacities for self-direction. Looked at this way, developmental relationships can both buffer the impact of stress and provide a pathway to motivation, self-efficacy, learning, and further growth.

A strong web of relationships between and among students, peers, families, and educators, both in the school and in the community, represents a primary process through which all members of the community can thrive. Schools can be organized to foster positive developmental relationships through structures and practices that allow for effective caring and the building of community. These include at least the following:

The contexts for development, including schools and classrooms, influence learning. This is especially important because the cues from our social and physical world determine which of our 20,000 genes will be expressed and when. Over our lifetimes, fewer than 10% of our genes actually get expressed. When settings are designed in ways that support connection, safety, and agency, a positive context for development of potential is created.

The contexts for development, including schools and classrooms, influence learning. This is especially important because the cues from our social and physical world determine which of our 20,000 genes will be expressed and when. Over our lifetimes, fewer than 10% of our genes actually get expressed. When settings are designed in ways that support connection, safety, and agency, a positive context for development of potential is created.

The brain is a prediction machine that loves order; it is calm when things are orderly and gets unsettled when it does not know what is coming next. Learning communities that have shared values, routines, and high expectations—that demonstrate cultural sensitivity and communicate worth—create calm and ignite the other part of the brain that loves novelty and is curious. Children are more able to learn and take risks when they feel not only physically safe with consistent routines and order, but also emotionally and identity safe, such that they and their culture are a valued part of the community they are in.

In contrast, anxiety and toxic stress are created by negative stereotypes and biases, bullying or microaggressions, unfair discipline practices, and other exclusionary or shaming practices. These are impediments to learning because they preoccupy the brain with worry and fear. Instead, co-creating norms; enabling students to take agency in their learning and contribute to the community; and having predictable, fair, and consistent routines and expectations for all community members create a strong sense of belonging.

To achieve an environment in which belonging and safety are principal features, a school can consider the following:

To engage learners in rich learning experiences that develop brain architecture as well as formal knowledge and deep understanding, educators should provide meaningful and challenging work for all students within and across core disciplines, including the arts, music, and physical education. This includes opportunities for students to develop their knowledge in ways that build on their culture, prior knowledge, and experience and help learners discover what they can do and are capable of.

To engage learners in rich learning experiences that develop brain architecture as well as formal knowledge and deep understanding, educators should provide meaningful and challenging work for all students within and across core disciplines, including the arts, music, and physical education. This includes opportunities for students to develop their knowledge in ways that build on their culture, prior knowledge, and experience and help learners discover what they can do and are capable of.

Students learn best when they are engaged in authentic activities and are collaboratively working and learning with peers to deepen their understanding and to transfer knowledge and skills to new contexts and problems. They will be empowered to solve these problems through formal and informal feedback from peers and adults as they engage in activities.

Because learning processes are very individual, teachers need opportunities and tools to come to know students’ experiences and thinking well, and educators should have flexibility to accommodate students’ distinctive pathways to learning, as well as their areas of significant talent and interest. Approaches to curriculum design and instruction should recognize that learning will happen in fits and starts, which requires flexible scaffolding and supports, differentiated strategies to reach common goals, and methods to leverage learners’ strengths to address areas for growth. A school can consider the following:

Neuroscience advances show that parts of the brain are cross-wired and functionally interconnected. As a result, learning is integrated: There is not a math part of the brain that is separate from the self-regulation or social skills part of the brain. For students to become engaged, effective learners, educators need to develop students’ content-specific knowledge alongside their cognitive, emotional, and social skills. These skills, including executive function, growth mindset, social awareness, resilience and perseverance, metacognition, and self-direction, can and should be taught, modeled, and practiced just like traditional academic skills and should be integrated across curriculum areas and across all settings in the school. To achieve these aims, schools can incorporate the following structures and practices:

Neuroscience advances show that parts of the brain are cross-wired and functionally interconnected. As a result, learning is integrated: There is not a math part of the brain that is separate from the self-regulation or social skills part of the brain. For students to become engaged, effective learners, educators need to develop students’ content-specific knowledge alongside their cognitive, emotional, and social skills. These skills, including executive function, growth mindset, social awareness, resilience and perseverance, metacognition, and self-direction, can and should be taught, modeled, and practiced just like traditional academic skills and should be integrated across curriculum areas and across all settings in the school. To achieve these aims, schools can incorporate the following structures and practices:

All children need support and opportunity. And all students have unique needs, interests, and assets to build upon, as well as areas of vulnerability to strengthen without stigma or shame. Thus, learning environments should be designed to include many more protective factors than they currently do, including health, mental health, and social service supports as well as opportunities to extend learning and build on interests and passions. Building comprehensive and integrated supports will tip the balance toward an environment where students feel safe, ready, and engaged.

All children need support and opportunity. And all students have unique needs, interests, and assets to build upon, as well as areas of vulnerability to strengthen without stigma or shame. Thus, learning environments should be designed to include many more protective factors than they currently do, including health, mental health, and social service supports as well as opportunities to extend learning and build on interests and passions. Building comprehensive and integrated supports will tip the balance toward an environment where students feel safe, ready, and engaged.

To do this, opportunities for exploration, intervention, and growth must be plentiful, rich, and extensive to meet students where they are and help them discover their purpose and direction. Opportunities and supports nurture students’ agency, help them discover what motivates them, inspire them, and help them advocate and contribute to changing suboptimal conditions they may experience.

In addition, all students will experience different needs at different times. It is therefore helpful to organize integrated supports as tiers. Universal supports (i.e., Tier 1) are those available in every classroom and include Universal Design for Learning, prioritization of relationships, fair and just discipline practices, and a culture of safety and belonging. Integrated supplemental supports (i.e., Tier 2) provide learners with additional support when needed and may include small group work with the teacher or a tutor on specific skills, or outreach from a counselor or social worker to support a current need. More individualized and intensive supports (i.e., Tier 3) are those that respond in a sensitive and timely manner to student readiness, wellness, and needs. To do so, Tier 3 interventions personalize supports and experiences in school, out of school, and with families through special education services; health or mental health services; or more intensive family assistance, including re-engaging disconnected learners.

Having comprehensive and integrated supports like these in place can allow schools to extend learning; enable safety and belonging; and address students’ unique health, mental health, and social service needs. A school can consider the following:

Conclusion

Our framework for these principles is built on a theoretical foundation of how children learn and develop that is inherently optimistic and recognizes the power of educators, families, youth developers, and other practitioners from diverse disciplines to create conditions that:

- support the talents and agency of each child;

- respect the culture and assets of the community; and

- create personalized opportunities for growth.

Building better conditions for learning and development will yield the robust equity we all seek in our education systems. Today, education systems must be willing to embrace what we know about how children learn and develop. The core message from diverse sciences is clear: The range of students’ academic skills and knowledge—and, ultimately, students’ potential as human beings—can be significantly influenced through exposure to highly favorable conditions. These conditions include learning environments and experiences that are intentionally designed to optimize whole child development.