Launching into the heart of the conference, Anisha pops open a large three-ring binder and tells her parents what she is most proud of, what she found most challenging, and how she has grown from her work in her humanities, science, learning seminar, and art classes. Next, Anisha reflects on her contribution to the school community and on her overall goals for the quarter, saying:

This year I have contributed to the school community by building stronger friendships, creating shared spaces with my peers, participating in class more regularly, conducting community service, and volunteering to do small classroom jobs such as passing out papers. In the beginning of the year, I didn’t raise my hand to share my thoughts during class, but now I participate and share out and speak up, especially when we’re doing work in small groups. I have grown so much from the start of the school year when I was really nervous to speak up.

Using sentence stems generated by her advisor to scaffold the flow of the conference, Anisha explains, “Resources that helped me feel more confident were my math teacher and my table group because they encouraged me and offered me some strategies to use, such as setting a goal to raise my hand once per class and to share ideas with my teachers before or after class even if I wasn’t able to speak up publicly.” And, finally, she ends with, “This goal in life and school is important because if I don’t learn to participate in my own learning, I will never get over feeling nervous and I won’t grow.”

Anisha’s parents sit across from her, beaming with pride, and politely inquire if they can now interject with questions.

This web of strong relationships is a cornerstone of the school’s academic success. Gateway Public School serves a diverse group of about 800 students, most of them students of color from low-income families, in both a middle and a high school. The school was founded to serve students with disabilities in an inclusion model and continues to serve a disproportionate number of such students. About half of incoming students read below grade level when they start 6th grade.

Because of its strong system of supports, the high school has a graduation rate of 98%,1 and 96% of students have matriculated to college since the high school was founded in 1998.2

Overview of Positive Developmental Relationships

The student-led conference profiled in the vignette above is just one of the many ways that Gateway Middle School in San Francisco fosters close connections among students, teachers, and families as partners in the learning process. Anisha’s experience and the science of learning and development converge on the essential understanding that positive developmental relationships are the active ingredient in any effective child-serving system.

Positive relationships enable children and adolescents to manage stress, ignite their brains, and fuel the connections that support the development of the complex skills and competencies necessary for learning success and engagement. Such relationships also simultaneously promote well-being, positive identity development, and students’ belief in their own abilities.

Parents from all backgrounds want their children to attend schools where their children are well known, cared for, respected, and empowered to learn. Families with financial privilege often choose private school settings for their children that provide small, personal learning communities where their children will be known and where relationships are prioritized. All parents hope that their children will be able to feel safe and valued at school, and all children deserve such contexts for learning. Recent brain research suggests that parents are right: Secure relationships build healthy brains that are necessary for development and learning.

Having secure relationships at school does not just mean that children are treated kindly by adults. It also means that students are nurtured through those relationships to develop independence, competency, and agency—that they grow to become confident and self-directed learners and people. As we saw in Anisha’s student-led family conference, Anisha is developing the reflective skills to understand and lead her own learning, to assess her strengths and weaknesses, and to create goals. Anisha’s skills and growth mindset are cultivated by a web of positive relationships that connect her with her teacher, her parents, and her school community.

These kinds of relationships provide the avenue to learning and growth and buffer individuals’ negative experiences and stress. A strong web of relationships between and among students, peers, families, and educators, both in the school and in the community, represent a primary process through which all members of the community can thrive.

What the Science Says

Human relationships are the essential ingredient that catalyzes healthy development and learning. Relationships that are reciprocal, attuned, culturally responsive, and trustful are a positive developmental force in the lives of children. For example, when an infant reaches out for interaction through eye contact, babble, or gesture, a parent’s ability to accurately interpret and respond to their baby’s cues affects the wiring of brain circuits that support skill development. These reciprocal and dynamic interactions literally shape the architecture of the developing brain and support the integration of social, affective, and cognitive circuits and processes, not only in infancy but throughout the school years and beyond. When children interact positively with teachers and peers, qualitative changes occur in their developing brains that establish pathways for lifelong learning and adaptation.

Adult relationships best support students when they are attuned and responsive to all aspects of the child’s experience, including—importantly—their cultural experiences. All children need to feel that they belong and are valued in their classroom and school community. If children experience anxiety about whether they will be valued for who they are, which may accompany stereotype threats associated with students’ identities (race, class, language background, immigration status, dis/ability, sexual orientation, or other marginalized status), the cognitive load this creates undermines their achievement. When educators build cultural competence—including their knowledge of and respect for students’ cultural backgrounds and personal experiences— research shows that they are better able to understand the verbal and nonverbal communication of students and respond appropriately, helping all students to be respected and heard, and supporting stronger achievement.

Relationships are multidirectional and interdependent. As a child is influenced by other people, they are also capable of changing the beliefs and actions of others as well. If a child learns how to communicate effectively, this shapes the ways others respond to them. This extends to the multiple relationships in a student’s life. For instance, if a child’s parents communicate with the child’s teachers, this interaction may influence the child’s development. When relationships are structured to be mutually reinforcing and multidirectional, like those at Gateway Middle School, positive effects on development are the outcome.

Developmental relationships allow children to grow in trust, competence, and agency. That relationships are important is not new information to educators, families, or researchers. Relationships engage children in ways that help them define who they are, what they can become, and how and why they are important to other people. However, not all relationships are developmentally supportive. In a developmental relationship, the emotional connection is joined with adult guidance that enables children to learn skills, grow in their competence and confidence, and become more able to perform tasks on their own and take on new challenges. Children increasingly use their own agency to develop their curiosity and capacities for self-direction. As developmental relationships enable the young person to grow, the balance of power shifts toward the student, as shown in the vignette with Anisha. Looked at this way, developmental relationships can both buffer the impact of stress and provide a pathway to motivation, self-efficacy, learning, and further growth.

What Schools Can Do

When schools focus on strengthening relationships, they create the conditions for raising academic standards by giving students more challenging and meaningful work and, at the same time, enabling them to engage in the work productively in the context of those relationships. With scaffolding and support, students’ social and emotional growth and character development can become an integral part of academic learning, and students can be empowered to become more self-directed as learners.

Schools that have been redesigned to foster positive developmental relationships have found new organizational approaches that enable school staff, educators, students, and families to know each other well in a context of trust and collaboration. They also enable students to become active participants in their relationships and in the creation of their learning environment and experiences. These schools adopt both structures and practices that allow for effective caring and the building of community. These include at least the following:

In many schools, creating strong relationships may require reimagining and restructuring key parts of the school designs inherited from an educational system put into place nearly 100 years ago. Large comprehensive schools in which teachers see 150 students a day in 45-minute periods provide little opportunity for teachers to come to know all of those students well. Many students can go unnoticed. Those experiencing challenges or trauma may have no opportunity to get help from a caring adult.

Fortunately, many schools have been redesigned to center relationships, and a number of school networks have been established that have adopted similar features, which they now help other schools to adopt. Evidence shows that these redesigned schools have stronger attendance, achievement, and graduation rates than others serving similar students.4 (See “Where to Go for More Resources” at the end of this section). One such network with a strong record of school success is the Institute for Student Achievement, a national nonprofit organization that partners with districts to redesign high schools. Among the strategies adopted by the network schools—also common among other redesigned schools—are:

- Small school sizes, typically 300 to 500 students.

- Advisors assigned to each student for multiple years who serve as an advocate; connect with families; and hold advisory classes, like family groups, that provide academic support as well as social and emotional learning opportunities.

- Teaching teams in which staff work in groups to develop shared norms and practices so that a cohort of interdisciplinary teachers (English, math, science, and social studies) teaches the same students. In some schools these teachers loop with the students to the next grade.

- Explicit relationship building leveraged through advisories and teaching teams.

- Attention to student voice and needs through student engagement in research and student-initiated projects on topics of concern.

- Student leadership in advisories and clubs.

- Outreach to families that includes frequent communication with parents in multiple ways.

Another school network that combines these types of relationship-building practices, EL Education (formerly Expeditionary Learning), offers a curriculum focused on inquiry learning in English language arts, combined with social and emotional learning and character development. Schools implementing the EL Education model across the nation, typically serving students of color in low- income communities, outpace district and state averages on state assessments and graduation rates.5 There is no single way to achieve these goals, but district and school leaders can consider a variety of structures and practices that can enable, rather than undermine, positive relationships.

Below, we describe the structures and practices schools can implement to design schools that foster positive developmental relationships, organized into three areas: (1) personalizing relationships with students, (2) supporting relationships among staff, and (3) building relationships with families.

Personalizing Relationships With Students

“[The teachers] treat us like people with emotions. We have real relationships with our teachers. We want to do our work because we care about our teachers.”

Strong relationships among and between teachers and students at schools in the Internationals Network support rich academic learning, language acquisition, and student well-being. Photo provided by Internationals Network.

- looping,

- advisory systems,

- block scheduling,

- longer grade spans, and

- small school size and/or small learning communities.

Looping

Looping teachers with the same students for more than one year enables continuity in relationships and stronger achievement gains.

Looping can occur when an elementary teacher works with the same students in 4th and 5th grade, for example, or when a secondary teacher has the same students for 9th- and 10th-grade English language arts. When teachers stay with the same students for more than one year through looping, they can come to know the students and families well, uncover how students learn, build trust, and gain time for productive instruction, since effective instructional strategies that address children’s individual needs can carry over from one year to the next. Furthermore, the reduced anxiety, understanding of the classroom context, and heightened trust enable more productive learning. The strong relationships and deep knowledge of student learning supported by these longer-term relationships between adults and children can substantially improve achievement, especially for lower-achieving students,7 and can also boost student and teacher attendance while lowering disciplinary incidents and suspensions, grade retention, and special education referrals.8

Teachers in such settings report a heightened sense of efficacy, while parents report feeling more respected and more comfortable reaching out to the school for assistance. As a teacher at Benjamin Franklin Intermediate School in Daly City, CA, noted:

Through looping, I’ve had my students in math and science class for 2 years now. What strikes me most is the progress of students who often get lost in the system— the shy ones who now ask questions because they trust me, the unmotivated ones who now come in for help because they know I’ll be supportive, and the defiant ones who now recognize that I’m an ally who cares for them. These are the kids who need adults’ support the most, but it takes them the longest to develop relationships. Looping gives us the time to make these relationships happen.9

While looping has been most often used in elementary schools, it is also found in some high schools. In the Internationals Network, a successful school model for newcomers who are new English learners, an interdisciplinary team of four core content area teachers stays with a group of 80–100 students for 2 years, with a counselor attached to the cohort.10 These personalized supports are especially important in the Internationals schools, where as many as one third of students arrive as unaccompanied minors and struggle to manage housing, food, health care, and other basic supports, as well as learning the language and customs of a new country (as illustrated in this vignette of Oakland International High School).

Advisory systems

“Our advisors are really cool; they make sure we do the work. If they see that I am trying to get it done, they help me prioritize. They don’t let people fail.”

Advisory systems can ensure that each student has an in-school “family” and a strong relationship with a caring adult who is an advocate, supporter, and link to a student’s family.

In effective advisory systems, each teacher advises and serves as an advocate for a small group of students (usually 15–20), often over 2 to 4 years. Teachers facilitate an advisory class that meets regularly to support academic progress, teach social and emotional skills and strategies, and create a community of students who support one another. In a distributed counseling function, advisors support students on academic and nonacademic issues that arise and serve as the point person with other faculty teaching the same student. The advisor functions as a bridge between student, school, and home so that students are provided the supports they need in a coherent way that allows them to navigate school in a productive and positive manner. Many studies finding positive effects of small schools or learning communities note the importance of advisories in enabling these effects.12

Block scheduling

Block scheduling creates more time for teachers to collaborate and build relationships with students.

Block scheduling is the practice of having fewer, longer class periods in a given day to reduce teachers’ overall pupil load and lengthen time for instruction. For example, instead of six 45-minute class periods, schools might schedule only three 90-minute classes each day. Each teacher sees half as many students, and students see fewer teachers. This smaller pupil load allows teachers to provide more attention to each student and to engage in more in-depth teaching practices. Block scheduling has been found to support improved behavior and achievement for students, including higher grades and higher rates of course completions, especially when courses continue for a full year and teachers use the longer class periods to implement teaching strategies that support inquiry, help students obtain directed practice, and personalize instruction. When a school adopts block scheduling for part or most of the day, it is important that teachers be given ample time and professional learning support for transforming their pedagogies. Longer lessons are effective when teachers make good use of the time by bringing in active challenges, problem-solving, hands-on work, group work, presentations of thinking and learning, and synthesis of learning. During a transition to block scheduling, it is helpful to have teachers share their learning and best practices with each other as they find good ways to engage students with more complex thinking and work.

Longer grade spans

Longer grade spans allow for closer, longer-term relationships and smoother school transitions.

Schools with longer grade spans (e.g., k–8 or 6–12) are also found to be more effective in supporting student outcomes than schools with shorter grade spans, as they help to establish and build upon close relationships among and between school staff, students, and families. Many studies have found that school transitions have a negative effect on student achievement: In particular, the transition to middle school at 5th or 6th grade has been found to decrease achievement in reading and math and, moreover, sharply increase the odds of dropping out.14 These results are consistent across multiple states, as well as in urban, suburban, and rural areas. This may be in part the result of the transition itself and in part the result of the departmentalized structures that many middle schools adopt, which create larger pupil loads for teachers and more disruption for students. At a vulnerable time in young adolescence, when children should be developing greater competence and confidence to support their growing autonomy, they may flounder when placed into an environment that reduces their opportunities for attachment and introduces them to the system of tracking. The tracking system is known to cause teachers to draw comparisons between students and to cause students to draw comparisons with their peers, comparisons that include negative attributions about competence and intelligence.

Small school size and/or small learning communities

Small school size or small learning communities within larger schools allow students to be well known and allow educators to create a community within the school with shared norms and practices.

Practices to strengthen relationships between educators and students

Personalizing structures that enable students to be known are most effective when they are joined with practices that build positive school culture, community, and trust.

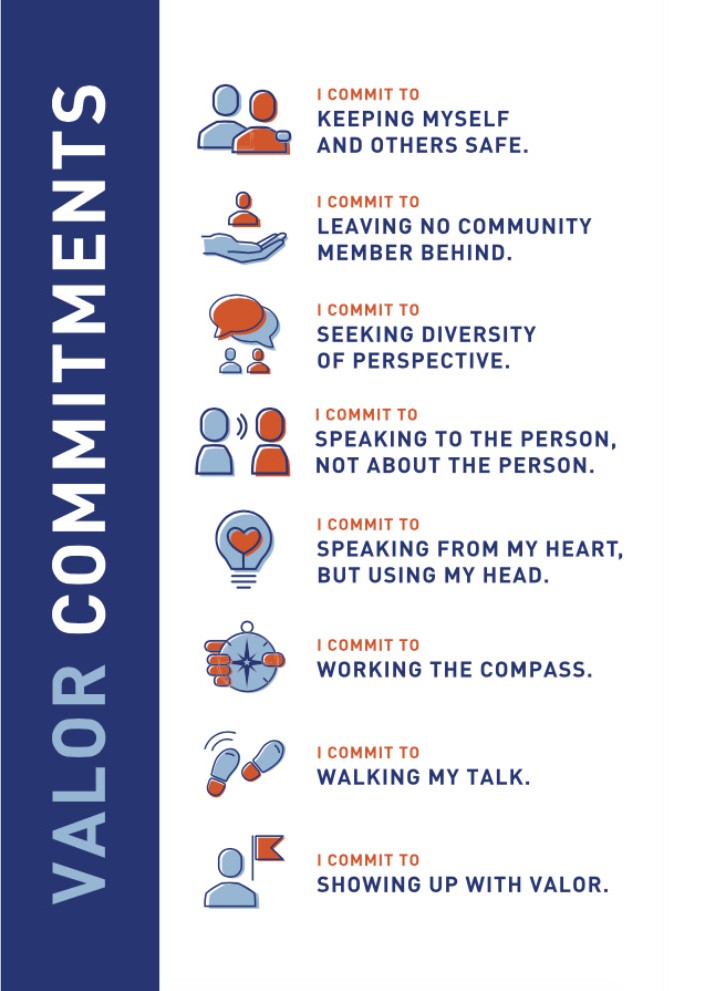

Structures that enable students to be known and valued by each other and by adults provide a foundation for healthy academic and personal growth. But structures alone are not sufficient. They must be joined to a schoolwide commitment to build a healthy learning community in which adults and children value and model positive behavior, exhibiting habits like respect, responsibility, courage, compassion, and integrity (see “Environments Filled With Safety and Belonging” for more on building a caring school community).

Practices that build trust. Turnaround for Children has built a continuum of strategies for building trust that focuses on several interrelated dimensions of relationship building:

- The quality of interactions: All students predictably experience interactions with adults that are marked by interest, inquiry, support, affirmation, and empathy. Schoolwide prioritization of relationship building results in frequent reflection, collaboration, and continuous improvement around the quality of adult–student interactions.

- Personalized understandings and reflections: Adults get to know all students as whole individuals by actively listening, asking questions, and providing opportunities for students to speak about their interests, experiences, and beliefs, recognizing the culturally grounded experiences of each student as a foundation on which to build knowledge and connections within and beyond the classroom.

- Choice and voice: Meaningful opportunities for student choice and voice are regularly and seamlessly integrated into classroom routines, structures, and practices (e.g., providing a choice of how to practice a skill or demonstrate mastery, providing input on a classroom policy). All students are given increasing levels of responsibility and autonomy as they grow, as adults support them through both successes and setbacks. Students lead conversations and projects, give feedback to adults, and co-construct classroom and school culture.

Practices that seek to ensure all students thrive. Particularly in large secondary schools, it is possible for students to “hide” while they struggle with academic or emotional issues. Even in elementary schools and small secondary schools, it can be challenging to track the struggles that students are experiencing internally or in their home lives. To address this, schools use a range of strategies to catch students before things unravel. Pairing older students with younger students (e.g., 5th-graders with 1st-graders; high school seniors with freshmen) as reading buddies or mentors can build relationships that are positive for both. In some schools, students who are struggling with emotional or behavioral challenges are connected with a caring adult—a counselor, social worker, nurse, or aide, or even a school custodian or administrator—to spend time, not as a disciplinary consequence but as a therapeutic experience (i.e., getting some love and attention).

Many schools also create ways to review their progress regularly to determine strategies for supporting students who may be struggling with academics, attendance, or behavior—or who may have experienced a traumatic event. When students are flagged for high concern, the first step is to determine who on the staff knows that student well (e.g., their home life, health, interests) and then to learn what is needed to wrap around that student with supports. Often, teaching teams meet for child reviews to support problem-solving and to figure out the best outreach and resources for individual needs.

This how-to guide is based on the pioneering “Every Student Every Day” advising approach of Phoenix Union High School District in Arizona, where every student in the district’s 21 high schools is connected to a caring adult who monitors their progress, attendance, and social and emotional well-being.

Supporting Relationships Among Staff

Educators in Sanger Unified School District consistently collaborate to improve student learning and to build strong staff culture. Photo provided by Sanger Unified School District.

A positive and supportive staff culture is the foundation of a school climate that enables positive developmental relationships. Student culture follows staff culture. If staff are not respectful, compassionate, and inclusive with each other, if they do not model a growth mindset in their learning and a commitment to equity and social justice, how can we expect students to display these habits? Recent research makes clear that mindset interventions with students are effective when those students have teachers who model productive mindsets; when they do not, the positive effects of the intervention tend to evaporate.22 Furthermore, research on teacher effectiveness shows that teachers become more effective over time in collegial settings where they have opportunities to collaborate with and learn from one another.23

This means that school leaders need to prioritize structures and practices that build a healthy professional learning community for staff, enabling staff to strengthen relationships that support each other in their work and to continue their professional and personal growth. It also requires ongoing efforts to be sure everyone on the staff feels respected, heard, and valued.

Schools in the United States often need new structures that provide opportunities for staff to develop collective expertise about students and a shared developmental approach. Expertise in teaching—as in many other fields—comes from a process of sharing, attempting new ideas, reflecting on practice, and developing new approaches. However, U.S. school structures were built on the notion that teachers are only working when they are in front of students. Thus, many American teachers spend their Sunday nights sitting at their kitchen tables, all by themselves, creating their lessons for the week. This model has resulted in U.S. teachers teaching more hours per week and year than any other teachers in the industrialized world and having less time for individual and collective planning. International surveys show that the average teacher around the world has, on average, 8 hours more per week for planning and collaboration than the average teacher in the United States.24

Structures that help cultivate positive relationships among school staff include:

- structures and time for staff collaboration within and across disciplines, such as grade-level or subject-matter teams;

- dedicated time and structures for professional learning and decision-making; and

- meetings and events to build positive school culture.

These structures are enabled to be effective by the way in which they are used and implemented in practice, as described in greater detail below.

Collaborative planning

“There is structured time every Wednesday [for teachers] to meet as a family and just talk. When I think back to my previous teaching experience, we didn’t have this collaborative time, and so it was kind of like every teacher was in their own little world. There’s just this expectation that teachers are communicating. And that time builds culture, and I think it has really helped me to be able to know what is going on.”

Collaboration time for teachers enables them to develop a collective perspective, create a more coherent curriculum, address problems of practice, and ensure that students do not fall through the cracks.

Relationship-centered schools commit time and resources to collaborative planning and asset- based professional development. This supports both more thoughtful and effective teaching within the classroom and greater coherence across courses and grade levels, as well as relational trust among staff members. These practices have been found to retain teachers in schools, contributing to staff stability, and to increase teaching effectiveness and gains in student achievement.26

One important strategy that supports collaboration and student-centered practices in secondary schools is interdisciplinary teaming, through which a group of teachers shares a group of students and has common planning time. This structure allows teachers to share their knowledge about students in planning curriculum to meet student needs, while creating more continuity in practices and norms, which supports students emotionally and cognitively. As one synthesis of research notes:

Effective interdisciplinary teaming reduces the levels of developmental hazard in educational settings by creating contexts that are experientially more navigable, coherent, and predictable for students. Interdisciplinary teaming can also create enhanced capacity in schools for transformed instruction through enabling the coordination and integration of the work of teachers with each other, including in instruction, and as ongoing sources of professional development and support for each other.27

Some middle and high schools combine courses in interdisciplinary team block schedules in which teachers from two or more courses share a common group of students—such as a combined math and science course taught by one teacher alongside a combined English language arts and social studies course (often called humanities) taught by another teacher. Often these courses are co-planned with other math or science or humanities teachers so that all teachers get the benefits of each other’s disciplinary expertise, even as they are teaching smaller groups of students for longer blocks of time individually. Team block schedules can further reduce the total number of individuals with whom students and teachers interact while also fostering greater collaboration among teachers to coordinate curriculum.

Professional learning and decision-making

Opportunities for shared learning and decision-making across the school—including distributed leadership, staff meetings, events, rituals, and retreats—foster staff relationships and school coherence.

Many schools have allocated a block of time for the purposes of shared learning and decision- making once a week toward the end of a workday—usually about 2 hours—by banking instructional time during the week (i.e., adding 30 minutes of instructional time on other days). Students may be involved in internships or in clubs or extracurriculars offered by community members and organizations during that time.

Involving staff in decision-making about school practices and professional development fosters both commitment to the decisions that are made and coherence in practices across the school. There is evidence that teacher participation in school decision-making can lead to improved academic achievement for students.28 Engagement in decision-making at the school level models the collaborative work that effective teachers expect from their students (and, indeed, the democratic process of the larger society) and enables small schools to make significant improvements in their practice with the full endorsement and engagement of all members of the school community.29

Distributed leadership is also important: In addition to teachers serving as interdisciplinary leaders, grade-team leaders, or department heads, staff can lead the committees that interview and hire staff, plan and implement professional development, and manage other functions that cut across teaching teams. These smaller groups of staff work on specific issues, bringing them back to the whole staff when policy decisions must be made. This shared school governance maintains the coherence and unity of purpose in the work of the school. It can also help eliminate and prevent actions based upon misinformation about the school’s values, policies, or practices. At some schools, committees and work groups have changing memberships to increase representation and involvement, as well as to create opportunities for people to develop shared perspectives and learn from one another. As one elementary teacher at San Francisco Community School described:

There is a level of trust that gets built over time because everything is with other teachers.… The leadership model means we are always together. It’s a lot of shared responsibility, and it is really supportive.30

Staff meetings, events, rituals, and retreats can also be used to build positive staff culture. Teaching students and managing schools can be relentless work, discouraging at times, and being part of a staff community that is positive and supportive can be a key to staff resilience and efficacy. If all staff gatherings are dedicated to getting the business of school done, with no attention to the social and emotional health of staff members and their professional and personal growth, meetings can end up wearing staff down more than supporting them. Meetings, events, rituals, and retreats can be used to build positive staff spirit—learning together, eating together, celebrating together, and sharing their personal lives. Staff development work that is respectful and meaningful for staff can also play that role.

In addition, it is important to create safe and productive contexts for staff to grapple together with a range of issues, including whether staff from all races, cultures, and backgrounds feel respected and heard in the school community. That work may include courageous conversations, perhaps facilitated by external experts, to grapple with how racism, sexism, and stereotypes affect staff members and staff culture (see “Environments Filled With Safety and Belonging” for more on creating identity-safe learning experiences).

Practices that build productive relationships among staff

Collaborative learning among staff can be used to build both shared teaching expertise and relational skills.

Structures to foster relationships can only be effective if the adults in the school have the knowledge and relational skills to realize the potential of those structures for building positive developmental relationships. Collaborative practices for developing these skills are asset based, avoid blame, and provide explicit skills and tools.

This report details the benefits and challenges of creating time and capacity for teacher collaboration and shared learning, along with detailing how Hillsdale High School redesigned its master schedule to facilitate the school’s collective mission and goals to support collaboration and relationships.

Building Relationships With Families

Family engagement provides opportunities for deeper knowledge of children and greater alignment between home and school. Building strong relationships between the school and the family increases academic outcomes for students across all grade levels. Schools can cultivate such partnerships by developing structures that support school–family relations as part of the core approach to education. These structures can include:

- tools for outreach and regular communication to actively engage families as partners;

- student–teacher–family conferences that are scheduled around families’ availability; and

- dedicated time and resources for home visits (virtual or in person).

The practices and strategies that can be used to fulfill the promise of these structures to successfully build meaningful relationships with families are described below.

Tools for outreach and regular communication with families

“You call, email, text, whatever method they give you to get in contact with them, and the teachers use it. They check it. They answer it. That’s my personal experience. I have not contacted any of my son’s teachers or principal without an immediate answer, and that’s pretty sweet.”

Tools for outreach and positive, regular communication with families can actively engage families as partners, including student–teacher–family conferences and home visits.

Schools that have successfully engaged parents and guardians have moved beyond traditional approaches, which often exclude families that are working long hours, are unable to get to the school easily at inflexible hours, or do not speak English as a native language. Among the tools that are used successfully by many schools are:

- Regular, positive communication with families about what the school or classroom is doing and how a child is doing through regular postings on the school website in multiple languages, as well as phone calls, emails, and text messages, translated into home languages whenever possible.

- Face-to-face meetings online as well as in person and, to the extent possible, at times matched to parent or guardian availability. Choosing times thoughtfully and providing babysitting for in-person meetings can increase family participation. Many schools have also learned that their shift to online communications with families through online town hall meetings, posted videos, and one-on-one parent conferences have solved transportation and child care problems and sharply increased family participation during the pandemic.

- Sending books and other materials home for reading, math, science, art, or other activities. This can enable families to support children in their learning (e.g., shared book reading with specific strategies and tips; math games to play at home; how to use walks in the neighborhood or trips to the grocery store for learning).

Periodic student–teacher–family conferences, scheduled around families’ availability, engage families in their student’s learning while creating student agency and ownership over their own learning.

Several innovations on traditional parent–teacher conferences can greatly improve their ability to engage families and support learning:

- holding them more frequently (e.g., two or three times a year) at times that family members can attend (which requires rearranging teachers’ time and finding compensation for teachers);

- using student-led conferences at which young people are active facilitators and participants in teacher–family discussions; and

- using them as opportunities to learn from family members and plan together for children’s goals, rather than communicating judgments about how children are doing.

Such meetings are designed to help teachers learn from parents about their children, review student progress and set goals, and provide an opportunity for parents to see and hear in their child’s own words what they are learning. As this section’s opening vignette, “Student-Led Conferences at Gateway Middle School,” illustrates, when student-led conferences are held midway through the school year, they allow students to formally share their cumulative work across the semester with their family members and teachers. Such conferences help students build important skills for meaningful learning, including agency and self-advocacy, while also encouraging self-reflection and metacognition (see “Development of Skills, Habits, and Mindsets” for more on promoting such skills).

Home visits can proactively build relationships with families throughout the year. Home visits, conducted in person or virtually, allow for proactive, intentional engagement with families and enable teachers and families to learn about one another with the aim of developing a true partnership to benefit students. Parent–teacher home visits have been found to be a particularly effective strategy for engaging families, informing teachers, and combating implicit bias, particularly where staff experiences are not rooted in the same community and cultural backgrounds as their students.32 Home visits enable teachers or staff members to:

- proactively establish trusting relationships with families;

- learn about the parents’ aspirations and insights about their children;

- communicate information (such as school schedules, ways of working, academic approaches, and health and safety protocols); and

- allow for students to be connected to additional supports or resources in order to be successful and learn.

Home visits and other family communications are most effective when they are conducted not just at the beginning of the school year but more than once during the year, such as in conjunction with key milestones or transition periods (e.g., between terms or before or after a long holiday break). (See “Where to Go for More Resources” at the end of this section for additional resources for home visits.)

Practices to build productive relationships with families

Diverse families are more successfully engaged as partners with valued expertise when schools embrace shared power and responsibility.

There is no single strategy or silver bullet, but several successful means for engaging parents and increasing achievement have been found when teachers and school staff work together with families as partners to develop common strategies for working with children, seeking parents’ advice and knowledge as well as working together through the logic of specific approaches. Helping parents learn how to read with their children and how to ask about and check in on students’ homework or projects can be helpful, even if parents do not have the knowledge or language background to offer specific help on these activities. Students can be the readers and information providers, knowing that their family members care about their progress.

The Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships

This web page compiles resources for educators, families, and communities to help implement home visit programs, including tools for getting started, training, and outreach.

This guide identifies essentials for motivating and supporting students and for creating strong partnerships with families, including advisors for all, staff teaming, and virtual home visits, accompanied by tools and resources.

Summary

The development and implementation of these kinds of structures and practices has been ongoing for more than 40 years in many schools across the country that have already redesigned their work. Currently, national and local networks such as Big Picture, the Boston Center for Collaborative Education, EL Education, Envision Education, the Internationals Network, Institute for Student Achievement, the Middle College National Consortium, New Tech, and others are made up of schools in which developmental relationships are a central organizational feature (noted in “Where to Go for More Resources”).

All children have the potential to thrive, and all children are vulnerable to the challenges they encounter in their experiences and contexts. In communities, in homes, and in schools, relationships characterized by sensitivity; attunement; consistency; trustworthiness; and social, emotional, and cognitive stimulation provide the protection as well as the scaffolds through which children grow as students and as whole human beings.

As illustrated throughout this section, positive developmental relationships are an essential organizing principle for equitable and empowering whole child education. When students and teachers have close, caring relationships, students feel more comfortable taking risks on behalf of learning and stretching to do things they have never done before. They will have a safe space in which to express themselves honestly and make sense and meaning of the things they are learning and experiencing, whether those are supportive or difficult.

Beyond individual teacher–student relationships, a strong web of relationships between and among students, peers, families, and educators, both in the school and in the community, can provide the opportunities to build, and in some cases rebuild, essential trust and create the collective will to enable equitable experiences, opportunities, and outcomes for each and every child.

Where to Go for More Resources

This how-to guide is based on the pioneering “Every Student Every Day” advising approach of Phoenix Union High School District in Arizona, where every student in the district’s 21 high schools is connected to a caring adult who monitors their progress, attendance, and social and emotional well-being.

This report details the benefits and challenges of creating time and capacity for teacher collaboration and shared learning, along with detailing how Hillsdale High School redesigned its master schedule to facilitate the school’s collective mission and goals to support collaboration and relationships.

This web page compiles resources for educators, families, and communities to help implement home visit programs, including tools for getting started, training, and outreach.

This guide identifies essentials for motivating and supporting students and for creating strong partnerships with families, including advisors for all, staff teaming, and virtual home visits, accompanied by tools and resources.

Endnotes

- 1 California Department of Education. (2018). California School Dashboard school performance overview: Gateway High, 2018. https://www.caschooldashboard.org/reports/38684783830437/2018; California Department of Education. (2018). 2017–18 Local Educational Agency accountability report card: San Francisco Unified. https://www2.cde.ca.gov/larc/leacontact.aspx?d=38684780000000&y=2017-18 (accessed 08/04/19).

- 2 Gateway Public Schools. (n.d.). Our impact. https://www.gatewaypublicschools.org/results (accessed 08/04/19).

- 3 Berkowitz, R., Moore, H., Astor, R. A., & Benbenishty, R. (2016). A research synthesis of the associations between socioeconomic background, inequality, school climate, and academic achievement. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 425–469; Wang, M-T., & Degol, J. L. (2016). School climate: A review of the construct, measurement, and impact on student outcomes. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 315–352.

- 4 Darling-Hammond, L., Ross, P., & Milliken, M. (2006). High school size, organization, and content: What matters for student success? Brookings Papers on Education Policy, 9, 163–203. www.jstor.org/stable/20067281; Hernández, L. E., Darling-Hammond, L., Adams, J., & Bradley, K. (with Duncan Grand, D., Roc, M., & Ross, P.). (2019). Deeper learning networks: Taking student-centered learning and equity to scale. Learning Policy Institute; Lee, V. E., Bryk, A. S., & Smith, J. B. (1993). The organization of effective secondary schools. Review of Research in Education, 19, 171–268; Friedlaender, D., Burns, D., Lewis-Charp, H., Cook-Harvey, C. M., Zheng, X., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2014). Student-centered schools: Closing the opportunity gap. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education.

- 5 EL Education. (n.d.). By the numbers. https://eleducation.org/impact/school-design/by-the-numbers (accessed 11/25/20).

- 6 Friedlaender, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2007). High schools for equity: Policy supports for student learning in communities of color. The School Redesign Network at Stanford University. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/scope-high-schools-equity-policy-supports-student-learning-communities-color.

- 7 Bogart, V. (2002). The effects of looping on the academic achievement of elementary school students. East Tennessee State University; Hampton, F., Mumford, D., & Bond, L. (1997). Enhancing urban student achievement through family-oriented school practices. ERS Spectrum, 15(2), 7–15.

- 8 Burke, D. L. (1997). Multi-year teacher/student relationships are a long-overdue arrangement. Phi Delta Kappan, 77(5), 360–361; George, P., & Alexander, W. (1993). “Grouping Students in the Middle School” in George, P., & Alexander, W. M. (Eds.). The Exemplary Middle School (2nd ed., pp. 299–330). Harcourt Brace.

- 9 Darling-Hammond, L., Alexander, M., & Price, D. (2002). 10 features of good small schools: Redesigning high schools, what matters most. School Redesign Network at Stanford University. (p. 5).

- 10 Roc, M., Ross, P., & Hernández, L. E. (2019). Internationals Network for Public Schools: A deeper learning approach to supporting English learners. Learning Policy Institute; Darling-Hammond, L., Ancess, J., & Ort, S. W. (2002). Reinventing high school: Outcomes of the coalition campus schools project. American Educational Research Journal, 39(3), 639–673.

- 11 Friedlaender, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2007). High schools for equity: Policy supports for student learning in communities of color. School Redesign Network at Stanford University. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/scope-high-schools-equity-policy-supports-student-learning-communities-color.

- 12 Darling-Hammond, L., Ross, P., & Milliken, M. (2006). High school size, organization, and content: What matters for student success? Brookings Papers on Education Policy, 2006/2007, (9), 163–203; Felner, R. D., Seitsinger, A. M., Brand, S., Burns, A., & Bolton, N. (2007). Creating small learning communities: Lessons from the project on high-performing learning communities about “what works” in creating productive, developmentally enhancing, learning contexts. Educational Psychologist, 42(4), 209–221.

- 13 Zalaznick, M. (2020, June 26). How student–teacher relationships can prevent a lost school year. District Administration. https://districtadministration.com/how-student-teacher-relationships-can-prevent-a-lost-school-year/.

- 14 Rockoff, J. E., & Lockwood, B. B. (2010). Stuck in the middle: Impacts of grade configuration in public schools. Journal of Public Economics, 94(11–12), 1051–1061; Schwerdt, G., & West, M. R. (2013). The impact of alternative grade configurations on student outcomes through middle and high school. Journal of Public Economics, 97, 308–326; Simmons, R. G., & Blyth, D. A. (1987). Moving Into Adolescence: The Impact of Pubertal Change and School Context. Aldine.

- 15 Darling-Hammond, L., Ross, P., & Milliken, M. (2006). High school size, organization, and content: What matters for student success? Brookings Papers on Education Policy, 2006/2007, (9), 163–203.

- 16 Lee, V. E., Bryk, A. S., & Smith, J. B. (1993). The organization of effective secondary schools. Review of Research in Education, 19, 171–267.

- 17 Bloom, H. S., & Unterman, R. (2014). Can small high schools of choice improve educational prospects for disadvantaged students? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 33(2), 290–319; Wasley, P. A., Fine, M., Gladden, M., Holland, N. E., King, S. P., Mosak, E., & Powell, L. C. (2000). Small schools: Great strides, a study of new small schools in Chicago. Bank Street College of Education.

- 18 California Department of Education. (2019). California School Dashboard school performance overview: Vista High. https://www.caschooldashboard.org/reports/37684523738705/2019 (accessed 11/25/20).

- 19 School Redesign Network of Stanford University. (2005). Windows on Conversions case study: Hillsdale High School. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/2024-03/Windows_on_Conversions_Hillsdale_SCOPE_CASESTUDY.pdf.

- 20 California Department of Education. (2019). California School Dashboard school performance overview: Hillsdale High. https://www.caschooldashboard.org/reports/41690474133070/2019 (accessed 11/25/20).

- 21 Cornwall, G. (2018, May 14). How being part of a ‘house’ within a school helps students gain a sense of belonging. KQED MindShift. https://www.kqed.org/mindshift/50960/how-being-part-of-a-house-within-a-school-helps-students-gain-a-sense-of-belonging.

- 22 Dweck, C. S., Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2014). Academic tenacity: Mindsets and skills that promote long-term learning [White paper]. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. http://studentexperiencenetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Academic-Tenacity-White-Paper.pdf; Rattan, A., Good, C., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). “It’s OK—Not everyone can be good at math”: Instructors with an entity theory comfort (and demotivate) students. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(3), 731–737; Paunesku, D., Walton, G. M., Romero, C., Smith, E. N., Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2015). Mind-set interventions are a scalable treatment for academic underachievement. Psychological Science, 26(6), 784–793.

- 23 Jackson, C. K., & Bruegmann, E. (2009). Teaching students and teaching each other: The importance of peer learning for teachers. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(4), 85–108; Kraft, M., & Papay, J. P. (2014). Can professional environments in schools promote teacher development? Explaining heterogeneity in returns to teaching experience. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36(4), 476–500.

- 24 Jerrim, J., & Sims, S. (2019). The Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018. OECD.

- 25 Lewis-Charp, H., & Law, T. (2014). Student-centered learning: City Arts and Technology High School. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education. https://uj9a82.p3cdn1.secureserver.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/SCOPE-Student-Centered-Learning-City-Arts-final.pdf.

- 26 Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators. Learning Policy Institute.

- 27 Felner, R. D., Seitsinger, A. M., Brand, S., Burns, A., & Bolton, N. (2007). Creating small learning communities: Lessons from the project on high-performing learning communities about “what works” in creating productive, developmentally enhancing, learning contexts. Educational Psychologist, 42(4), 209–221.

- 28 Smylie, M. A., Lazarus, V., & Brownlee-Conyers, J. (1996). Instructional outcomes of school-based participative decision making. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 18(3), 181–198.

- 29 Darling-Hammond, L., Alexander, M., & Price, D. (2002). 10 features of good small schools: Redesigning high schools, what matters most. School Redesign Network at Stanford University. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/media/4279/download?inline&file=10_Features_Redesigning_High_Schools_SCOPE_REPORT.pdf.

- 30 Wentworth, L., Kessler, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2013). Elementary schools for equity: Policies and practices that help close the opportunity gap. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education. https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/elementary-schools-equity-policies-and-practices-help-close-opportunity-gap.pdf.

- 31 Lewis-Charp, H., & Law, T. (2014). Student-centered learning: City Arts and Technology High School. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education. https://uj9a82.p3cdn1.secureserver.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/SCOPE-Student-Centered-Learning-City-Arts-final.pdf.

- 32 McKnight, K., Venkateswaran, N., Laird, J., Robles, J., & Shalev, T. (2017). Mindset shifts and parent teacher home visits. RTI International. https://pthvp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/mindset-shifts-and-parent-teacher-home-visits.pdf.

References

For more information on the research supporting the science and pedagogical practices discussed in this section, please see these foundational articles and reports:

- Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context. Applied Developmental Science, 23(4), 307–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1398649(link is external).

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B. J., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791(link is external).

- Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(1), 6–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1398650(link is external).