The lesson of the day in a 9th- and 10th-grade biology class at San Francisco International High School focuses on a central question: “Should soda have a tax?” The class of 25 students, roughly divided between 9th- and 10th-graders, includes several students in both grade levels who are recent arrivals and have been in the United States for 6 months or less. Even the students who have been at San Francisco International the longest have only been in the United States for 18 to 24 months. In this school and others that are part of the Internationals Network across the country, newcomers who arrive without knowing the English language graduate, enter college, and succeed at much higher rates than their peers, having experienced an inquiry-based curriculum that engages them in meaningful and challenging tasks that they revise to meet high standards of performance.

Like other project-based learning environments, instruction for this heterogeneous class is connecting academic topics, such as biology, to real-world topics—in this case, nutrition and policy. The veteran teacher, Patricia, has built extensive scaffolds into her lesson that were designed to meet students at their English language acquisition, content knowledge, and skill development levels. She moves through the classroom engaging individual students, small groups of students, and the whole class.

She intentionally leverages the assets that her students have brought to the classroom, particularly their native language fluency. The core question was written in English and in the five other languages spoken by the students in the class to give students an immediate starting point in their native languages that allows them to engage with the content questions even if their English language skills were not yet developed to the point of allowing them to do so fully in English.

The teacher uses other techniques that allow students to use their native languages to support themselves and one another in engaging with the rigorous content. For example, throughout the classroom, students use Google Translate to translate words from Spanish, Arabic, and other languages. In contrast to classrooms in which students’ native languages are minimized or seen through a deficit lens, students leverage their home languages to make meaning of complex grade-level academic content. With students from multiple linguistic backgrounds, English is the common language and the language of formal academic discourse. Yet English is not positioned as the only valuable language. The assets-based classroom environment makes students feel comfortable taking risks to speak, read, and write in English, but they also use their native languages as a valuable tool to be harnessed and developed.

The teacher also takes steps to make instruction and content accessible and to further students’ vocabulary and writing development. For example, she prominently displays visuals from earlier lessons that students have labeled, and she has research articles and documents readily available so that students can access them through the inquiry process. In addition, each portion of the lesson is carefully chunked into discrete sections to allow students to understand the content and to apply their emerging English skills. For instance, students engage with pictures relevant to the soda tax debate and connect those pictures with academic English words they have learned in previous lessons (e.g., “glucose”). One chunked exercise includes the following stages:

- Each student chooses one picture and labels it in English with scientific terms that have previously been taught.

- In small groups, students discuss the pictures using English: What did other people write? What did it make you think?

- Next, using the labeled pictures from their groups, students individually write “a complex sentence—a big sentence” in English that can be used in their final essays.

- In doing so, students need to use the English words “but,” “because,” or “so.” For example: “When you don’t eat, the glucose decreases because your body uses the energy.”

During the lesson, the teacher walks throughout the room meeting individually with students to make sure that they are receiving the supports they need to successfully engage with the language and content. She also constantly moves her hands, draws pictures on the board, points to visual scaffolds on the walls, and makes motions that have meaning, as if she is playing a 90-minute game of charades with the students. She also has developed a series of sounds that are not English words but that the students associate with an action (e.g., a sound that encourages students to look at their peers who are speaking or a sound that encourages students to use sentence starters that are on the walls). This simple yet effective method seems to help ease the cognitive load for her students who are doing far more than the typical native English speaker would be doing in such a class. She repeatedly reminds her students of her expectations for participation and reinforces participation and structural routines to keep students engaged.

Eventually, students build from these smaller tasks to craft thesis statements and ultimately write persuasive essays in English that support their position on the value of soda taxes. While the development of academic English related to the content is clearly scaffolded through these steps, the teacher also has an explicit focus on science, engaging the students on both the science behind how sugary drinks affect humans and the social science behind their impact on communities. Over multiple weeks, students develop the content knowledge and the English literacy skills needed to engage orally and in writing on the topic in sophisticated ways.

Overview of Rich Learning Experiences

The classroom profiled in the vignette above provides a window into the pedagogical approaches, curricular designs, and assessment practices that enable students to deeply understand disciplinary content and develop skills that will allow them to solve complex problems; communicate effectively; and, ultimately, manage their own learning. It illustrates how a teacher can skillfully blend inquiry-based learning with strategic elements of direct instruction using multiple modalities of learning that help students draw connections between what they know and what they are trying to learn. By using a well-scaffolded and meaningful task that relates to students’ lives, this teacher helps her students advance their understanding of human biology, the English language, and the writing of persuasive essays while affirming their cultural and linguistic identities. By providing them with means to facilitate their own learning—through the use of multiple languages, tools like Google Translate, and opportunities to collaborate and share their observations—the teacher also promotes student agency and a growth mindset: Students know how to get better, and they see themselves advancing with effort.

San Francisco International High School is just one of many innovative schools that have demonstrated how standards can be better taught and learned when students are motivated by the opportunity to dive deeply into serious questions, demonstrating what they have learned by showing and explaining the studies, products, and tools they have developed. This kind of learning process can, with the right kind of teaching supports, help students develop the executive functioning and metacognitive skills needed to plan, organize, manage, and improve their own work and become more self-directed—skills that are essential both for this more complex educational world and for the world of college and careers beyond.

Schools and classrooms like these embody an important fact: Learning is a function both of teaching—what is taught and how it is taught—and of student perceptions about the material being taught and about themselves as learners. Students’ beliefs and attitudes have a powerful effect on their learning and achievement. Motivation can be nurtured by skillful teaching that provides meaningful and challenging work, within and across disciplines, that builds on students’ culture, prior knowledge, and experience, and that helps students discover what they can do in their zone of proximal development—that is, what the child can do with a range of robust supports. Students learn best when they are engaged in authentic activities and collaborate with peers to deepen their understanding and transfer of skills to different contexts and new problems. Rich learning experiences can be supported by inquiry-based learning structures, such as projects and performance tasks, with thoughtfully interwoven opportunities for direct instruction and opportunities to practice and apply learning; meaningful tasks that build on students’ prior knowledge and are individually and culturally responsive; and well-scaffolded opportunities to receive timely and helpful feedback.

What the Science Says

As we have described in earlier chapters, brain architecture is developed by the presence of warm, consistent, attuned relationships; positive experiences; and positive perceptions of these experiences. Students need a sense of physical and psychological safety for learning to occur, since fear and anxiety undermine cognitive capacity and short-circuit the learning process. In addition, both neuroscience and research in the learning sciences have established that the brain actively pursues meaning by making connections and that it is stimulated by curiosities and inquiries that sustain interest and effort. The following key findings should inform educational practice.

Children actively construct knowledge based on their experiences, relationships, and social contexts. The brain develops and learning occurs through connections among neurons that create connections among thoughts and ideas. Learners connect new information to what they already know in order to create mental models that allow them to make sense of new ideas and situations. This process works best when students actively engage with concepts and when they have multiple opportunities to connect the knowledge to personally relevant topics and lived experiences, which is why culturally responsive practice is essential to the learning process. Effective teachers support learners in making connections between new situations and familiar ones, focus children’s attention, structure experiences, and organize the information children receive, while helping them develop strategies for intentional learning and problem-solving.1

Motivation and performance are shaped by the nature of learning tasks and contexts. In contrast to long-standing beliefs that ability and motivation reside in the child, the learning sciences demonstrate that children are motivated when tasks are relevant to their lives, pique their curiosity, and are well scaffolded so that success is possible. Tasks are made doable when they are connected to what is already known and chunked into manageable pieces that are not overwhelming. Children are motivated to learn by questions and curiosities they hold—and by the opportunity to investigate what things mean and why things happen. Humans are inquiring beings, and the mind is stimulated by the effort to make connections and seek answers to things that matter. Learning and performance are shaped by the opportunities to explore actions and ideas, receive feedback from others and the environment, and continue to refine and practice with assistance until mastery is achieved.

Transferable learning requires application of knowledge to authentic tasks. Much information that is learned in school is forgotten because it is not applied and used in ways that would allow it to be deeply understood. This “inert knowledge” is often the result of transmission-style teaching that offers disconnected pieces of information that are covered but not analyzed, memorized for a test but never actively used for a meaningful purpose. Knowledge that is transferable is learned in ways that engage children in genuine, meaningful applications of knowledge: writing and illustrating a book or story, rather than completing fill-in-the-blank worksheets; conducting a science investigation, rather than memorizing disconnected facts that might quickly be forgotten. Such learning engages higher-order skills of analysis, synthesis, critical thinking, and problem-solving and allows knowledge to be understood deeply enough to be recalled and used for other purposes in novel situations.

Students’ beliefs about themselves, their abilities, and their supports shape learning. Children’s expectations for success influence their willingness to engage in learning. These expectations depend on whether they perceive the task as doable and adequately supported as well as whether they have confidence in their abilities and hold a growth mindset. Those who believe they can succeed on a task work harder, persist longer, and perform better than those who lack that confidence. Those who believe they can improve through effort tend to be willing to try new things and to work harder when they encounter an obstacle, rather than giving up. These traits are developed in environments in which students believe they are viewed as competent and trust adults to support them, and in which they do not feel threatened by stereotyping, bullying, or other challenges. A child’s performance under conditions of high support and low threat will be measurably stronger than it is under conditions of low support and high threat. In such identity-safe environments in which cultural connections are made and adults are responsive and supportive, children’s academic performance climbs.

What Schools Can Do

To build on these understandings about learning, schools should provide meaningful, culturally connected work within and across core disciplines (including the arts, music, and physical education) that builds on students’ prior knowledge and experience and helps students discover what they can do and are capable of. The acquisition of more complex and deeper learning skills can be supported by creating authentic activities that engage students in working collaboratively with peers to deepen their understanding and transfer skills to different contexts and new problems.

Because learning processes are very individual, teachers need opportunities and tools to come to know students’ experiences and thinking well, and educators should have flexibility to accommodate students’ distinctive pathways to learning as well as their areas of significant talent and interest. Approaches to curriculum design and instruction should recognize that learning will happen in fits and starts that require flexible scaffolding and supports, differentiated strategies to reach common goals, and methods to leverage learners’ strengths to address areas for growth.

To be effective, these structures and practices for knowledge development need to be combined with the developmental relationships; features of positive learning environments; acquisition of social and emotional skills, habits, and mindsets; and integrated student supports discussed in other parts of this playbook. When they all come together, teaching and learning look much like they do in Ted Pollen’s 4th-grade classroom in New York City. (See “Rich Learning Experiences for Deep Understanding at Midtown West.”)

This short vignette illustrates many of the elements supporting rich learning experiences in a classroom and school that are grounded in the science of learning and development: Ted supports strong, trusting relationships in his classroom, as well as collaboration in the learning process, connections to prior experience, inquiry interspersed with explicit instruction where appropriate, and support for individualized learning strategies as well as collective learning. Authentic, engaging tasks with real-world connections motivate student effort and engagement, which is supported through teacher scaffolding and a wide range of tools that allow for personalized learning and student agency. Other scaffolds—like the charts reminding students of their learning processes and key concepts—support self-regulation and strategic learning while reducing cognitive load in order to facilitate higher-order thinking and performance skills. These also enable student self-assessment, as well as peer and teacher feedback that is part of an ongoing formative assessment process. Routines for reflection on and revision of work support the development of metacognition and a growth mindset.

Meanwhile, students’ identities as competent writers, scientists, and mathematicians are also reinforced, as their work dominates the walls of the classroom and is the focus of the learning process. All students feel they belong in this room, where they are learning to become responsible community members, critical thinkers, and problem-solvers together. A range of culturally connected curriculum units and materials supports that sense of inclusion, while a wide array of school supports reinforces that inclusion by addressing student and family needs in multiple ways and including families as partners in the educational process.

Like Midtown West, many schools have been developing curricular approaches that aim for deeper understanding that reflects the growing knowledge base about how people actually learn: by actively constructing knowledge through authentic learning experiences that build on students’ prior understanding and cultural funds of knowledge.2 However, a number of engrained structures from older factory-model school designs can get in the way of this quest. These include an overreliance on transmission teaching driven by pacing guides that assume students all learn in the same way, at the same pace, by passively listening and answering questions, rather than as active drivers of their own learning. The coverage expectations of current standardized tests, which are typically limited to multiple-choice questions, can reinforce this mode of teaching, even though evidence shows that students taught through deeper learning strategies do equally well on these tests but much better on assessments of higher-order thinking and performance skills.3

Other remnants include siloed courses in which students are expected to learn content in separate and often disjointed ways, making interdisciplinary connections and knowledge application less frequent,4 and tracking systems that sort students into different learning pathways based on determinations of their measured “ability.”5 Tracking—which typically also segregates students by race, class, language background, and dis/ability status—often shapes both the disciplinary and curricular content in which learners engage and the ways they are taught. Studies have shown that students in higher tracks often engage in richer and more meaningful learning approaches, while those assigned to lower tracks are offered more rote and passive learning with minimal opportunities for critical thinking.

As Table 4.1 suggests, teaching in the ways that children actually learn will, in many ways, require reimagining the purposes and accoutrements of school. Schools that are designed to unleash the genius within every child have replaced the standardized assembly line with greater personalization, grounded in the knowledge that each child’s identity, cultural background, developmental path, interests, and learning needs create a unique path for them. Students from diverse backgrounds engage in collaborative inquiry-based learning by pursuing questions and problems that matter to them and to their communities. Rather than memorizing facts and regurgitating them on a test, students synthesize existing knowledge, apply it to open-ended questions and complex problems, and create something of value for an authentic audience beyond school. Adults recognize that children are fiercely curious and have wonderful ideas and provide them with rich, deeper learning experiences in heterogeneous classrooms that cultivate their sense of belonging, self-efficacy, and purpose.

Table 4.1

Transforming Schools to Advance Rich Learning Experiences

|

Transforming from a school with … |

Toward a school with … |

|

transmission teaching of disconnected facts |

inquiry into meaningful problems that connect areas of learning |

|

a focus on memorization of facts and formulas |

a focus on exhibitions of deeper learning |

|

standardized materials, pacing, and modes of learning |

multiple pathways for learning and demonstrating knowledge |

|

a view that students are motivated—or not |

an understanding that students are motivated by engaging tasks that are well supported |

|

a focus on individual work; consulting with others is “cheating” |

a focus on collaborative work; consulting with others is a major resource for learning |

|

curricula and instruction rooted in a canonical view of the dominant culture |

curricula and instruction that are culturally responsive, building on students’ experiences |

|

tracking, based on the view that ability is fixed and requires differential curriculum |

heterogeneous grouping, based on the understanding that ability is developed in rich learning environments |

Supporting Diverse Learners Through Universal Design for Learning

Universal Design for Learning enables students to use multiple tools, forms of engagement, and modes of expression to demonstrate learning.

As Todd Rose notes in “The Myth of Average,” every human brain is different, and every path to learning will vary as well. A critical aspect of enabling success for diverse learners without labeling, tracking, and stigma is the use of multiple modalities of engagement and expression in the classroom—and the use of multiple representations that can connect to students’ different experiences and prior knowledge.

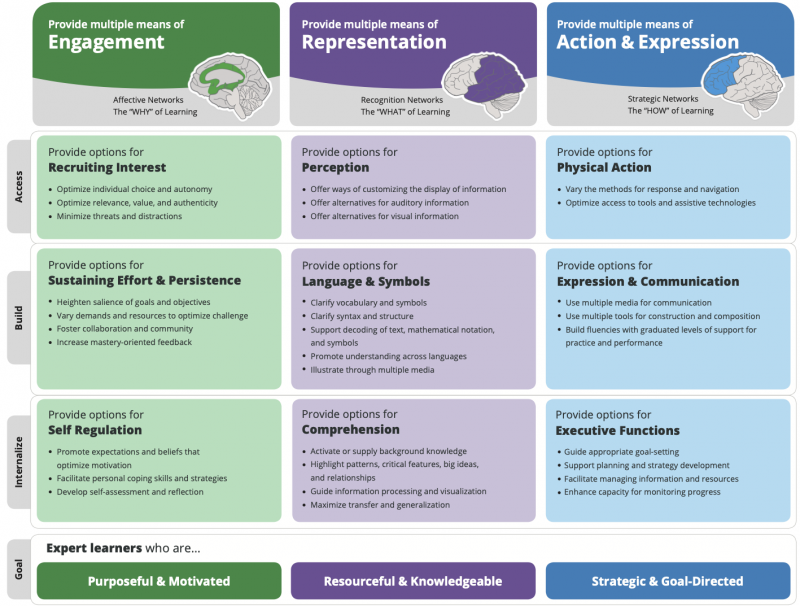

These approaches are codified by Universal Design for Learning, which establishes guidelines for improving and optimizing learning for all students based on scientific insights about learning and development. These guidelines provide concrete principles and strategies that can be applied to any subject or discipline to minimize barriers and maximize access to participation in meaningful learning opportunities. The guidelines are organized into three principles involving multiple means of engagement, representation, and action for accessing information: (1) building understanding, effort, and persistence; (2) internalizing learning through self-regulation and comprehension; and (3) creating options for expression, communication, and the building of executive function (e.g., goal setting, strategy development, monitoring progress) that can support learning (see Figure 4.1 below and this brief video, UDL at a Glance).

The Universal Design for Learning Guidelines

We saw these principles in action in the vignette of San Francisco International High School at the start of this section. In that vignette, we see how students who have different linguistic and cultural backgrounds, and differing amounts and kinds of formal education, worked collaboratively to tackle a common inquiry-based task with the use of multiple means of expression, supportive learning tools, and multiple representations by their teacher and their peers.

Building on these principles, many new school designs have created untracked approaches to teaching and learning that have led to much higher levels of success for diverse students. Such national and local school networks include Big Picture Learning, EL Education, Internationals Network, New Tech Network, Center for Collaborative Education, Envision Education, Linked Learning, and others. (See also “Development of Skills, Habits, and Mindsets” for more detail on collaborative learning strategies for engaging all learners.)

Scaffolding for Success

Learning scaffolds provide students with guidance that helps them master increasingly complex skills and knowledge while reducing cognitive load.

Engaging students in rich learning experiences that help them achieve conceptual understanding and the transfer of knowledge and skills requires scaffolding. Scaffolds are the structures and practices that provide students with the guidance that allows them to more readily master a task that is just beyond their current skill set or knowledge base.

Creating motivating tasks. Designing motivating tasks is the first step in scaffolding for success. When faced with a task, learners implicitly ask these questions as they decide whether they will take it on: “What am I being asked to do?” “Am I capable of tackling this task?” “Is this task meaningful to me?” “Does this have a purpose to me beyond school?” “What supports are available to me to wrestle with this task?” and “Do I feel safe in attempting to wrestle with this task?”6 When teachers work to make learning tasks relevant and clear and to make supports for learning transparent, they are enabling students to take the first step in the learning process.

When teachers work to make learning tasks relevant and clear and to make supports for learning transparent, they are enabling students to take the first step in the learning process.

Structuring performance. For a given task, students will need varying kinds of scaffolds that structure their work, depending on their prior experiences. So, for example, when writing a story, some students may benefit from sentence starters and hints about what happens in the beginning, middle, and end of the story, perhaps first told by drawing pictures. Others may understand the story structure and be ready for scaffolds to develop more complex sentences about how events in the story relate to each other in terms of sequence or cause and effect. At the end of the process, all children can complete the task in a way that advances their understanding and skills.

Well-designed and implemented scaffolds can provide the necessary supports that help students make meaning of what they are experiencing and propel learning and development forward. Implementing these supports well also involves communicating reassurance, helping students understand the habits of mind necessary to become proficient, and helping students understand the task’s relevance and how their personal trajectory toward competence could unfold.7

Using formative assessments. Targeted scaffolds for learning can be identified by teachers’ close observations of students’ work and by assessments that help pinpoint student thinking and performance relative to learning progressions and provide actionable guidance over time for how to move students along. These assessment tools and practices answer the key question, “Where are students now?” and provide the insights needed to enable effective support. These types of assessments are carried out as part of the instructional process for the purpose of adapting instruction and improving learning. Instead of focusing on if students indicate right or wrong answers, these assessments are designed to shed light on strategies for next steps that support ongoing improvement. Tools like the Balanced Assessment in Mathematics, the Developmental Reading Assessment, the Desired Results Developmental Profile, and The Fountas & Pinnell Literacy Continuum provide rich information for teachers about students’ thinking and performance that they can use to determine next steps in the learning process.

Providing tools. Teachers can also support student learning by providing strategies and tools that reduce cognitive load, freeing up more of the mind’s attention and working memory for higher-order thinking and problem-solving. Teachers can focus on big ideas and reduce expectations for memorization by providing easy ways for students to access information when they need it (e.g., notes, calculators, dictionaries, classroom posters, digital search tools). Teachers can chunk tasks by creating smaller steps that build knowledge toward larger accomplishments, rather than overwhelming students with too much new material at once. They can also give students opportunities to practice skills so that they become automatic, freeing up bandwidth for new material and more complex applications.

In the elementary classroom we visited earlier, the teacher, Ted, had worked with students to create many memory assists that were posted all over the classroom, including posters illustrating fractions problems the classroom had tackled and solved, a classroom constitution with shared norms, the definitions of figurative language, protocols that supported reading and writing activities, and other guidelines to support recall. These were often written in the students’ own words, codifying their learning so they could share it and go back to it as needed. All of these helped reduce cognitive load and supported student independence and confidence in building on their prior learning to tackle the complex learning they were undertaking.

Furthermore, assistive technologies such as audiobooks, electronic readers that can adjust the size and type of font, recording tools, dictation strategies, and other supports can help students with particular kinds of learning differences become successful in managing their learning and developing their abilities, rather than suffering from deficit frameworks that limit the advances they can make.

Supporting multiple ways to understand. Similarly, deeper learning is supported by techniques that provide ways to elaborate on and differently understand a concept, such as self-explanation and peer teaching. Asking students to explain and summarize ideas they have read aloud—or to teach concepts or skills to others—has been found to deepen their understanding and increase their achievement, as does asking them to represent information in multiple modalities. In mathematics, for example, asking students to represent quantitative information in multiple forms, such as with graphs and verbal explanations, can support robust understanding. Asking students to integrate abstract concepts and concrete examples into their explanations can deepen their comprehension while simultaneously providing richer data to teachers for assessment.

Another way schools can support students in deeply understanding ideas is to teach thematically in ways that help students see the connections among ideas and events across time, space, and disciplines and that provide students with many ways to explore, understand, and demonstrate their learning. For example, 10th-graders at Social Justice Humanitas Academy, a community school near Los Angeles, spend the first semester of their humanities class learning about various social movements, including the United Farm Workers movement, LGBTQ rights, and the #MeToo movement, among others. After exploring the varied dimensions of these movements, students write an essay and, in groups, create a play based on one of the movements. In doing so, students encounter the ideas of these movements and of social change from multiple perspectives while they use concepts and skills that they have learned in different classes and demonstrate what they’ve learned in different ways, using their research and writing skills, creativity, ability to perform, and ability to work in groups with their peers.

This article provides an overview of key principles and examples of differentiated instruction, Universal Design for Learning, and multicultural education, as well as a unit planner template to help educators put these components into action.

This center works with schools and communities, classroom teachers, students, and service organizations to address challenges of improving literacy and learning. Through its extensive research, it has generated resources that teachers, students, parents, and schools can use successfully to improve student achievement and literacy. This includes the Strategic Instruction Model, which points to teacher-focused and student-focused interventions that can effectively scaffold and bolster learning.

Developing Effective Inquiry-Based Learning

Inquiry-based approaches to learning enable students to take an active role in building knowledge and “learning to learn” by managing their own learning process.

Curriculum designs and instructional strategies can optimize learning by building on each student’s prior knowledge and experiences, connecting those experiences to the big ideas or schema of a discipline, and designing tasks that are engaging and relevant so that they spark students’ interests. A powerful way this is enabled is through inquiry-based learning, which requires students to take an active role in constructing knowledge as they work to solve a problem or probe a question. Inquiry may take place in a single day’s lesson or a long-term project, centered on a question or problem that requires conjecture, investigation, and analysis, using tools like research or modeling. The key is that—rather than just receiving and memorizing pieces of information that do not “stick”—inquiry provokes active learning and student agency through questioning, consideration of possibilities and alternatives, and application of knowledge.

The key is that—rather than just receiving and memorizing pieces of information that do not “stick”— inquiry provokes active learning and student agency through questioning, consideration of possibilities and alternatives, and application of knowledge.

In addition, providing opportunities for students to set goals and to assess their own work and that of their peers—often using rubrics that describe the dimensions of high-quality work and presentations that allow for deeper questioning and exchange—can encourage students to become increasingly self-aware, confident, and independent learners. Such strategies can challenge and support students to perform at the edge of their current abilities; help them transfer knowledge and skills to new content areas; and, ultimately, improve achievement.

Project-based learning is one form of inquiry learning that develops students’ knowledge and skills while they investigate meaningful problems or answer a complex question. Projects often center on real-world issues. They may incorporate interdisciplinary and standards-based tasks related to scientific or historical inquiry, close reading, extensive writing, and quantitative modeling and reasoning. They also often require that students present their work publicly.8

Components of successful project-based models include the use of strategic scaffolds to support learning—including clear steps that are checked along the way and rubrics that define the dimensions of high-quality work, structures for group work to ensure equal levels of participation, student choice that develops students’ ownership over the content and work, and explicit instruction and access to resources at critical junctures in the process.9

Performance assessments are often a key element of inquiry-based tasks. Such assessments require demonstrations of knowledge and skills as they are used in the real world. The on-the-road driver’s exam that supplements the multiple-choice test given to would-be drivers is one example of a performance assessment, as is the portfolio that architects submit to become certified. Students are typically asked to apply their knowledge and skills in creating a paper, project, product, presentation, and/or demonstration. These may be assembled and communicated through student portfolios or the systematic collection of student work samples, records of observation, scored papers or products, and other artifacts collected over time to demonstrate growth and achievement.

Performance assessments encourage higher-order thinking, evaluation, synthesis, and deductive and inductive reasoning while requiring students to demonstrate understanding.12 Furthermore, performance assessments can provide multiple entry points for diverse learners, including English learners and students with special needs, to access content and display learning.13 The assessments themselves are learning tools that also build students’ co-cognitive skills, such as planning, organizing, and other aspects of executive functioning; resilience and perseverance in the face of challenges; and a growth mindset that grows from the ongoing process of fine-tuning and improving the product. A growing number of schools and districts organize high school work around a portfolio of performance tasks that are assembled and exhibited to demonstrate the competencies they expect graduates to have developed.14

As seen in the story from Pasadena Unified, the several performance assessments presented and discussed in Maria’s senior defense were all shaped and fine-tuned over multiple iterations to achieve a standard of quality and to enable her to present with deep understanding. A long line of research shows that expert performance is related to opportunities for deliberate practice, which is coached through the provision of immediate feedback for a performance, opportunities to evaluate and problem-solve, and repeated attempts to refine the behavior or skill.15 As individuals become more expert, they can self-evaluate and identify strategies for improvement with less outside feedback. Opportunities for regular revision also help students develop a sense of confidence and competence as they see the improvements in their work, as well as a growth mindset they can carry into other contexts.

For deliberate practice and revision to occur, feedback should take place during the learning process, not at the end when teaching on that topic is finished, and teacher and students should have a shared understanding that the purpose of feedback is to facilitate learning. The quality of the feedback is key to its effects. Neither nonspecific praise nor negative comments support learning. Instead, gains occur when feedback focuses on features of the task and emphasizes the next steps needed to better achieve learning goals. Given that teachers cannot frequently meet one-on-one with each student, classroom practices should allow for students to display their thinking so the teacher will be aware of it and to learn to become increasingly effective critics of their own and each other’s work as they use rubrics and other tools to engage in self- and peer assessment.

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

Culturally responsive curricula and teaching build on and validate students’ diverse experiences to support learning, engagement, and identity development.

The practices we have described are most successful when students are in a safe environment and can see the connections to their own lives and experiences, which allows them to develop cognitive strategies and take greater agency over their learning. Culturally responsive learning environments celebrate the unique identities of all students while building on their diverse experiences to support rich and inclusive learning.16 This asset-based orientation rejects the idea that practitioners should be colorblind or ignore cultural differences. Instead, culturally responsive educators place students at the center by inviting their multifaceted identities and backgrounds into the classroom to inform curriculum design, instruction, and learning structures.17

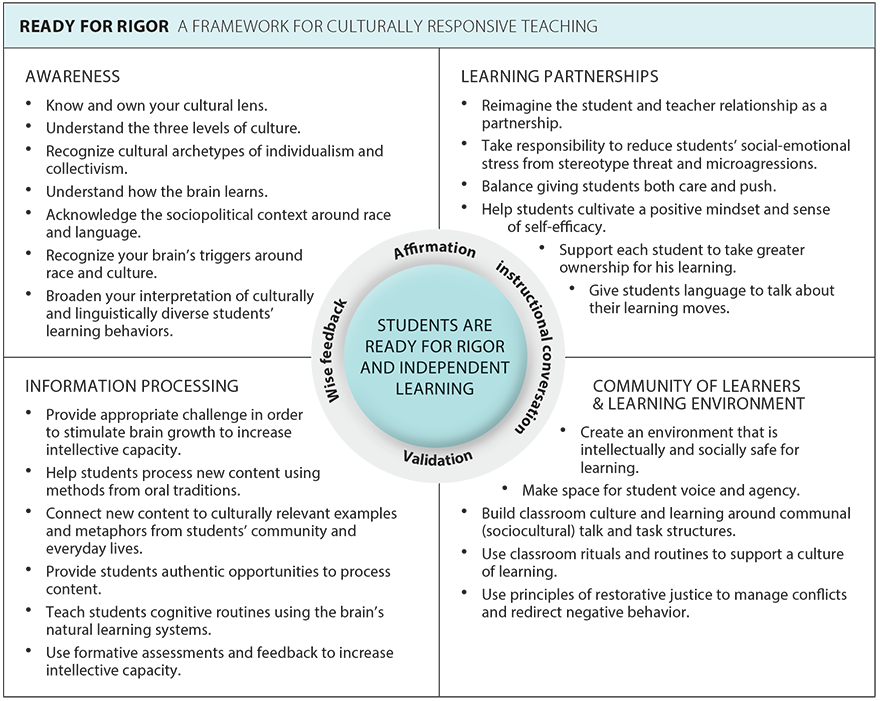

In her book Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain,18 Zaretta Hammond describes the goal of culturally responsive practices as getting students “ready for rigor.” (See Figure 4.2.) Her four strategies map closely onto the principles described in this playbook:

- Educator awareness of how the brain learns, of culture and context, and of students’ learning behaviors;

- Learning partnerships that cultivate positive mindsets, self-efficacy, and students’ ownership of learning and understanding of their own learning processes, while reducing stereotype threats in the classroom;

- Communities of learners in a supportive learning environment that is intellectually and socially safe, collaborative, focused on learning, and restorative; and

- Information processing supported through authentic, culturally connected tasks that build on students’ experiences and offer the right amount of challenge for what students are ready to do next, reducing cognitive load, and providing ongoing formative feedback and support.

Figure 4.2

Ready for Rigor: A Framework for Culturally Responsive Teaching

Culturally responsive practitioners recognize the importance of infusing students’ experiences into all aspects of learning.19 Doing so enables educators to be responsive to learners—both by validating and reflecting the diverse backgrounds and experiences young people bring and also by building upon their unique knowledge and schema to propel learning and critical thinking. Educators can also develop a culturally sustaining pedagogy by working to foster and nurture linguistic, literate, and cultural pluralism and equality.20 This creates a context of belonging for students that can counteract the deficit approaches to teaching and learning many students have experienced in contexts that have sought to minimize, penalize, or eradicate languages, literacies, and cultural ways of being that do not adhere to White, middle-class norms.

As culturally responsive, sustaining, and affirming pedagogical approaches center and celebrate diversity, they further belonging and inclusion21 and positively affect educational outcomes, including engagement in learning, racial identity development, and academic achievement.22 Furthermore, students from all backgrounds benefit from inclusive learning environments that honor and celebrate diversity. These settings can not only help all young people learn and embrace the diverse backgrounds and cultures that make up the fabric of U.S. democracy, but also cultivate their awareness and orientations toward issues of injustice.

Cultural responsiveness in learning settings can be cultivated by learning about students and the community through curriculum and instruction strategies that both surface and build on that knowledge. This includes practices for learning about and from students and their communities. To become a culturally responsive educator, a practitioner must find ways to know students well. This includes learning what students already know, in what areas they already demonstrate competence, and how they can bring that knowledge into the classroom context. (See “Positive Developmental Relationships” and “Environments Filled With Safety and Belonging” for descriptions of many strategies educators use to learn about students, ranging from home visits, to conversations with parents and students, to community walks, to journaling, surveys, classroom meetings, and community circles.)

Educators can learn about students’ strengths, interests, and concerns by providing opportunities for student voice and agency in the curriculum, including opportunities for students to talk and write about what they have experienced, know, think, care about, can do, and aspire to. Some schools do this in part through identity exploration and pursuit of community issues from a social justice perspective. These strategies teach educators about their students while allowing students to take ownership of the learning process and develop the critical thinking that enables them to challenge the status quo.

For example, at Social Justice Humanitas Academy (SJ Humanitas) near Los Angeles, students do just this by engaging in projects that help them learn concepts through the lens of their personal identities. For example, in a 9th-grade ethnic studies course, students spend time analyzing their personal histories. One SJ Humanitas teacher explained that the project allows students to move into later grades having “already looked at their history and their past, and the way that they see the world, and how [they can] become better for it.”23 Not incidentally, this project, like a similar autobiography in the 9th-grade humanities class at East Palo Alto Academy, teaches writing, reflection, and revision skills while teaching educators about their students in profound ways that can be built on throughout high school.24 In a related SJ Humanitas assignment, students read the memoir Always Running by Luis Rodriguez, in which the author recounts his experience as a young Chicano gang member surviving the dangerous streets of East Los Angeles. Students are asked to reflect on and write an essay about how the author overcame adversity and setbacks and achieved self-actualization (a core value at SJ Humanitas that guides students’ own reflections).

Another approach to enlisting student voice and agency is referred to as reality pedagogy, in which students take ownership of their learning by co-teaching each other and build from their cultural and homelife contexts by sharing and examining relevant artifacts. Teachers learn alongside students and engage them in co-designing the learning process, acknowledging their own limitations with academic content. This approach creates community, shared experience, and common knowledge among members of the classroom about one another and the communities they live in as it enables students to become responsible for their own learning, as well as one another, valuing and leveraging their different identities.25

Educators and students alike can learn in culturally responsive ways by engaging in community-based projects that ask them to critically analyze issues within their communities and take action to impact change.26 These projects are often launched by posing an essential question or equity-focused problem to students or by asking students to identify issues impacting them and their communities. Students have an authentic audience and purpose for their work, as we saw in Oakland High School’s collaborative project to improve safety associated with commuting to and from school. (See "Community-Connected, Project-Based Learning at Oakland High School" earlier in this section.)

Similarly, students at the UCLA Community School engaged in an interdisciplinary project as they transitioned to virtual schooling in response to COVID-19. This unit asked students to investigate the issues affecting their community in a 10-week inquiry process in which they sought to understand the disparate impact of the pandemic on communities of color and the responses of local students, teachers, and parents who have organized to work for justice in and beyond schools. After reading articles and reviewing current data and the latest research on the virus, students reported on how these issues were affecting them, their families, and their communities. Students were eager to participate because they were learning something they deeply cared about and could use to improve their own lives and those of their loved ones.

Ensuring that young people have rich learning experiences also requires culturally responsive content and materials that:

- reflect and respect the legitimacy of different cultures;

- empower students to value all cultures, not just their own;

- incorporate cultural information into the heart of the curriculum, instead of simply adding on at the margins; and

- relate new information to students’ life experiences.

Adopting culturally responsive curricula requires that practitioners acknowledge that what is taught in schools is not neutral; rather, curricula has the potential to either perpetuate or disrupt patterns of inequity and marginalization. With this understanding, educators can design and adopt programs that confront inequities resulting from discriminatory practices and policies, particularly those that have been perpetuated along economic, linguistic, and racial lines.27

A growing number of states and districts are beginning to offer supports to develop and implement high-quality curricula that are culturally relevant. Chiefs for Change highlights how several districts, such as Baltimore, MD; Palm Beach County, FL; and Philadelphia, PA, were already developing such materials prior to the pandemic, noting research suggesting that a culturally relevant curriculum has been found to increase student attendance, GPA, and course completion.

Using knowledge of students’ experiences, culturally responsive pedagogies also build bridges between students’ experiences and school content that draw on the familiar to tap into students’ prior knowledge and make it explicit to students to scaffold learning. Students often perform complex tasks outside of school that are not always displayed in school-type tasks. Additionally, their displays might not be recognized as demonstrating competence according to normative standards that dominate many classrooms.28 For example, calculations used on the basketball court may not initially carry into the mathematics class unless teachers are alert to support the transfer by building on this kind of real-world knowledge.

One study demonstrated how educators can illustrate symbolic meanings in literature by beginning with rap songs and texts the students know and carrying their insights into study of more formal canonic texts.29 Similarly, a study of the outcomes of inquiry-based instructional practices in mathematics classrooms serving students from low-income families found that linguistic, ethnic, and class inequalities were reduced when teachers contextualized problems and made them relevant to students’ lives, introducing new concepts through discussion and asking students to explain and discuss their thinking.30 These teachers achieved stronger outcomes by seeking to understand and support students’ thinking and inquiry in the context of rich, collaborative learning experiences, rather than narrowing the curriculum to rote-oriented algorithms, as often happens for students who have had less prior experience with the content.

Summary

To facilitate deep understanding and transfer of knowledge so that it can be used in new situations, teachers can combine explicit instruction with guided inquiry that allows students to engage in problem-solving in real-world contexts and can promote agency and metacognitive skills by asking students to evaluate, analyze, and create ideas, products, and solutions. By offering feedback along with self- and peer assessment throughout the learning process, and by encouraging students to revise their work, teachers can help students internalize standards and perceive evidence of their growing competence that supports a growth mindset. Providing opportunities for revision along with timely, constructive feedback on a regular basis encourages a mastery-oriented approach to learning. Combined with a learning environment that scaffolds learning, supports individual needs, and teaches in culturally responsive and affirming ways, this kind of teaching promotes students’ sense of belonging, self-confidence, and agency and ownership over their work, which in turn fosters motivation. Together, these approaches can help all students become self-sufficient and capable learners.

Where to Go for More Resources

This article provides an overview of key principles and examples of differentiated instruction, Universal Design for Learning, and multicultural education, as well as a unit planner template to help educators put these components into action.

This center works with schools and communities, classroom teachers, students, and service organizations to address challenges of improving literacy and learning. Through its extensive research, it has generated resources that teachers, students, parents, and schools can use successfully to improve student achievement and literacy. This includes the Strategic Instruction Model, which points to teacher-focused and student-focused interventions that can effectively scaffold and bolster learning.

Endnotes

- Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., Cocking, R. R., Donovan, M. S., & Pellegrino, J. W. (2004). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. National Academies Press.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). How People Learn II: Learners, Contexts, and Cultures. National Academies Press; Nasir, N. S., Lee, C. D., Pea, R., & McKinney de Royston, M. (2020). Handbook of the Cultural Foundations of Learning. Routledge.

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Adamson, F. (2014). Beyond the Bubble Test: How Performance Assessments Support 21st Century Learning. Jossey-Bass.

- Tyack, D., & Cuban, L. (1995). Tinkering Toward Utopia: A Century of Public School Reform. Harvard University Press.

- Oakes, J. (2005). Keeping Track: How Schools Structure Inequality (2nd ed.). Yale University Press.

- Lee, C. D. (2017). Integrating research on how people learn and learning across settings as a window of opportunity to address inequality in educational processes and outcomes. Review of Research in Education, 41(1), 88–111.

- Nasir, N. S., Rosebery, A. S., Warren, B., & Lee, C. D. (2014). “Learning as a Cultural Process: Achieving Equity Through Diversity” in Sawyer, R. K. (Ed.). The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences (pp. 686–706). Cambridge University Press.

- Vander Ark, T., & Schneider, C. (2014). Deeper learning for every student every day. Getting Smart. https://hewlett.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Deeper%20Learning%20for%20Every%20Student%20EVery%20Day_GETTING%20SMART_1.2014.pdf

- Barron, B., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2008). “How Can We Teach for Meaningful Learning?” in Darling- Hammond, L., Barron, B., Pearson, P. D., Schoenfeld, A. H., Stage, E. K., Zimmerman, T. D., Cervetti, G. N., & Tilson, J. L. (Eds.). Powerful Learning: What We Know About Teaching for Understanding (pp. 11–70). John Wiley & Sons; Ertmer, P. A., & Simons, K. D. (2005). Scaffolding teachers’ efforts to implement problem- based learning. International Journal of Learning, 12(4), 319–328; Hung, W. (2009). The 9-step problem design process for problem-based learning: Application of the 3C3R model. Educational Research Review, 4(2), 118–141; Kokotsaki, D., Menzies, V., & Wiggins, A. (2016). Project-based learning: A review of the literature. Improving Schools, 19(3), 267–277.

- Barron, B., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2008). “How Can We Teach for Meaningful Learning?” in Darling-Hammond, L., Barron, B., Pearson, P. D., Schoenfeld, A. H., Stage, E. K., Zimmerman, T. D., Cervetti, G. N., & Tilson, J. L. (Eds.). Powerful Learning: What We Know About Teaching for Understanding (pp. 11–70). Jossey-Bass; Boaler, J. (2002). Learning from teaching: Exploring the relationship between reform curriculum and equity. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 33(4), 239–258; Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., Cocking, R. R., Donovan, M. S., & Pellegrino, J. W. (2004). How People Learn. National Academies Press.

- Farrington, C. A., Roderick, M., Allensworth, E., Nagaoka, J., Keyes, T. S., Johnson, D. W., & Beechum N. O. (2012). Teaching adolescents to become learners: The role of noncognitive factors in shaping school performance—A critical literature review. Consortium on Chicago School Research.

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Adamson, F. (2014). Beyond the Bubble Test: How Performance Assessments Support 21st Century Learning. Jossey-Bass.

- Abedi, J. (2014). “Adapting Performance Assessment for English Language Learners” in Darling-Hammond, L., & Adamson, F. (Eds.). Beyond the Bubble Test: How Performance Assessments Support 21st Century Learning (pp. 185–206). Jossey-Bass.

- Maier, A., Adams, J., Burns, D., Kaul, M., Saunders, M., & Thompson, C. (2020). Using performance assessments to support student learning: How district initiatives can make a difference. Learning Policy Institute; Guha, R., Wagner, T., Darling-Hammond, L., Taylor, T., & Curtis, D. (2018). The promise of performance assessments: Innovations in high school learning and college admission. Learning Policy Institute.

- Ericsson, K. A. (2006). “The Influence of Experience and Deliberate Practice on the Development of Superior Expert Performance” in Ericsson, K. A., Charness, N., Feltovich, P. J., & Hoffman, R. R. (Eds.). The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance (pp. 683–703). Cambridge University Press.

- Stronge, J. H. (2018). Qualities of Effective Teachers. ASCD.

- Pledger, M. S. (2018). Cultivating culturally responsive reform: The intersectionality of backgrounds and beliefs on culturally responsive teaching behavior. UC San Diego.

- Hammond, Z. (2015). Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain. Corwin Press. See also: Hammond, Z. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching puts rigor at the center. Learning Professional, 39(5), 40–43. https://learningforward.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/culturally-responsive-teaching-puts-rigor-at-the-center.pdf.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teachers of African American Children (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93–97.

- Powell, J. A., & Menendian, S. (2016). The problem of othering: Towards inclusiveness and belonging. Othering & Belonging, 1, 14–39.

- Brown, M. R. (2007). Educating all students: Creating culturally responsive teachers, classrooms, and schools. Intervention in School and Clinic, 43(1), 57–62; Dee, T. S., & Penner, E. K. (2017). The causal effects of cultural relevance: Evidence from an ethnic studies curriculum. American Educational Research Journal, 54(1), 127–166.

- Ondrasek, N., & Flook, L. (2020, January 15). How to help students feel safe to be themselves. Greater Good Magazine. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_to_help_all_students_feel_safe_to_be_themselves.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Ramos-Beban, N., Altamirano, R. P., & Hyler, M. E. (2016). Be the Change: Reinventing School for Student Success. Teachers College Press.

- Emdin, C. (2016). For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood… and the Rest of Y’all Too: Reality Pedagogy and Urban Education. Beacon Press.

- Duncan-Andrade, J. M. R., & Morrell, E. (2008). The Art of Critical Pedagogy: Possibilities for Moving From Theory to Practice in Urban Schools (Vol. 285). Peter Lang.

- Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to Be an Antiracist. One World.

- Nasir, N. S., Rosebery, A. S., Warren, B., & Lee, C. D. (2014). “Learning as a Cultural Process: Achieving Equity Through Diversity” in Sawyer, R. K. (Ed.). The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences (pp. 686–706). Cambridge University Press.

- Lee, C. D. (2007). Culture, Literacy, and Learning: Taking Bloom in the Midst of the Whirlwind. Teachers College Press.

- Boaler, J. (2002). Learning from teaching: Exploring the relationship between reform curriculum and equity. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 33(4), 239–258.

References

For more information on the research supporting the science and pedagogical practices discussed in this chapter, please see these foundational articles and reports:

- Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context. Applied Developmental Science, 23(4), 307–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1398649.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B. J., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791.

- Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(1), 6–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1398650.