El Puente Academy for Peace and Justice was founded in New York City in 1993 by a neighborhood social justice organization working with the school system to turn around failure for students in the Southside neighborhood of Brooklyn—a community that was then one of the most violent in the city. By 2003, El Puente was recognized as one of the New York City Department of Education’s “Schools of Excellence,” and it continues to receive an A grade on the department’s official report card for its strong outcomes for students. The school’s 4-year, college-preparatory curriculum “promotes academic and intellectual mastery as well as holistic leadership development through a culturally relevant, standards-based curriculum that integrates community development projects.”

Developing community within and beyond the school is central to the school’s mission and is strengthened through several structures. All students belong to an advisory, which meets twice a week and focuses on life and relationships. Advisories engage in activities and games that build community as well as the serious business of analyzing relationships and their impact on students’ lives. For example, facilitators walk students through the creation of a relationship map. In the process of creating and working through their map, students begin to see which relationships add value to their lives and which might not. As one of the facilitators explained, students need to have silence, space, and no distractions because, “We’re really digging deep.” The activity is followed by a circle discussion, in which students share what they feel comfortable sharing. While advisory groups tend to be mixed gender, the school also has an all-girls advisory that focuses on topics that affect young women in particular, such as self-esteem, body image, drug abuse, emotional needs, and the use of language (e.g., how they talk to each other, the experience of code switching).

In addition to advisories, town hall meetings provide a gathering space for faculty and students, either all together or by advisory or grade level, to voice their concerns about existing practices and issues and make recommendations for constructive change. As such, these meetings demonstrate the relationship between empowerment and community change and exemplify social responsibility and community engagement by staff and students alike. Advisors help students prepare for these meetings in advance during their advisories, encouraging students to discuss issues they have with teachers, classes, or peers and to think about how to present such issues respectfully and constructively.

Advisors inform students about the presentation procedures, such as one mic (i.e., one speaker at a time). Students then write their talking points in advance, a practice that enables them to examine and reflect on their thoughts and feelings, as well as find ways to publicly express them that will be productive for themselves and the community. Assistant Principal Waleska Velez recounted one case in which students were able to express their objection to peers’ pejorative language about gay individuals. In order to ensure that all students have voice at a town hall meeting, students might be asked to record their issues on chart paper or use a strategy such as pass-the-ball to include everyone in the dialogue. Because town halls require students to navigate the relationship between their self-interest and their community’s needs, they provide opportunities for students to learn about the dialectic between the individual and common good and to exercise their skills as participants in this dialogue.

Overview of Environments Filled With Safety and Belonging

The vignette above illustrates how El Puente Academy prioritizes time and space in the master schedule for students and staff to come together regularly in advisory classes, town hall meetings, and other settings to foster students’ sense of belonging, ownership, and agency in the school. This type of environment is essential for student learning and development; it both buffers students from stress and adversity and provides safety and consistency, so that students can take risks, explore new experiences, and develop their identities. The culture staff and students build together has far-reaching effects because they “own it” as a community.

The environment of a school sets the tone through features of the physical environment, as well as how time and space are used and how relationships and experiences are created. This context sends messages about the value placed on the students and staff who work together in the school. What is important or unimportant, what is rewarded or sanctioned, who is powerful or powerless, and who is viewed as trustworthy or untrustworthy are all communicated by the environment. Broken or functional classroom furniture, current or outdated technology, and sufficient or limited instructional supplies communicate that those attending the school and those working in the school are important or unimportant, worth investing in or not. Access to and use of texts and instructional materials that acknowledge and reflect students’ backgrounds, culture, and interests send a message about the degree of student acceptance and belonging, the legitimacy of their cultures, and the importance of student voice in the school community. And an emphasis on restoring relationships rather than punishing missteps sends a message about whether students are viewed as worthy of trust and belong to the school community.

An environment can be rich in protective factors or contain significant risks to both children and staff. A positive learning environment (also referred to as a positive school climate) supports students’ growth across all domains of development—physical, psychological, cognitive, social, and emotional—while it reduces stress and anxiety that create biological impediments to learning. Such an environment takes a “whole child” approach to education, seeking to address the distinctive strengths, needs, and interests of students as they engage in learning. Educational settings that provide developmentally rich relationships and experiences, like El Puente Academy, can buffer the effects of stress or trauma, promote resilience, and foster healthy development and engagement in learning.

What the Science Says

The brain is a prediction machine that loves order: It is calm when things are orderly and gets anxious when things are chaotic or threatening. The brain wants to know what is going to happen next. We are constantly making predictions, unconsciously and at every moment of the day; positive, consistent routines allow our brains to predict what is coming next, which reduces the cognitive load needed to process new information. This new information fuels the learning process and the brain’s ability to be productive. When the brain knows what is coming next, it can plan for what it is going to do in response. However, if the environment is chaotic and unpredictable, the brain is less able to focus, concentrate, and remember. Environments designed with shared values, norms, and routines create calm, consistent, safe settings, which in turn, promote productivity, curiosity, and exploration.

Our environments influence the expression of our genes. Each of us has about 20,000 genes in our genome, yet in our lifetime, fewer than 10% of our genes will get expressed. Gene expression happens through a biological process called epigenetic adaptation, in which the environments, experiences, and relationships in our lives determine which genes are expressed. Thus, the life cycle of a child is shaped by the contexts he or she experiences and is not predetermined in a genetic program.

Children’s ability to learn and take risks is enhanced when they feel emotionally and psychologically safe; it is undermined when they feel threatened. The internal resources that children bring to learning—including prior knowledge and experience, integrated neural (social, emotional, and cognitive) processes, motivation, and metacognitive skills—are affected by the environments they experience. When children encounter trust, caring, and positive relationships with adults and peers, they can draw on these resources for learning. On the other hand, when children experience significant adversity or trauma, both their brains and their bodies are affected through the biological mechanisms of stress. This stress can become toxic when threats are constant. The surge of cortisol and adrenaline that is part of the stress response triggers hypervigilance and anxiety, reducing working memory and focus. Unless other supportive relationships and contexts are available, this process can affect the developing neural architecture that is critical for learning.

What Schools Can Do

“I’ve rarely met a student who couldn’t rise to the occasion, and if they weren’t rising to the occasion, it was probably because they needed extra support.”

A positive school context and community in which adults and students are dedicated to a shared vision of holistic student success is a core feature of a successful educational experience. Cultivating a supportive school environment that instills safety and belonging involves:

- building a safe and caring learning community, with consistent routines that allow students to be well known and well supported;

- developing restorative practices that are trauma-informed and healing-oriented; and

- fostering culturally responsive and inclusive learning experiences through which all students feel valued.

Whether consciously or not, a district’s or school’s policies and practices reflect current and older assumptions that have created customs and procedures over time, which sometimes have contradictory influences on the environment over time as well. For a school to achieve an environment in which belonging and safety are principal features, a good first step is to engage members of the school community to assess the assumptions reflected in current policies and practices to identify what changes are needed. (See, for example, this Climate Connections Toolkit and implementation rubric.) District and school leaders may ask: What are the behaviors we want to see members of our community enact? How do we support people to learn to behave in those desired ways? What is the evidence that current policies and practices produce the desired behaviors? This information can provide grist for the design of structures and practices that support safety and belonging in the school environment:

In order to design supportive environments filled with safety and belonging, some practices that many schools have inherited may need to evolve toward others that are more effective toward that end goal (see Table 3.1).

Transforming School Environments to Be Filled With Safety and Belonging

|

Transforming from a school environment in which … |

Toward a school environment in which … |

|

individual teacher discipline practices vary from class to class, communicating different expectations for relationships |

shared norms and values create consistency and positive experiences for students |

|

the focus is on moving individual students through academic curriculum only |

the focus is on community building as a foundation for shared social and academic work |

|

tracking systems convey differential expectations of students by race, class, language background, or disability |

heterogeneous classrooms with strong community norms and supports convey common expectations |

|

governance is by rules and punishments |

communities are built on shared responsibility that is explicitly taught and nurtured |

|

exclusionary discipline pushes students out of class and school |

restorative practices enable amends and attach students more closely to the community |

Building a Safe and Caring Learning Community

The foundations of a safe and caring learning community are:

- shared values and norms that are co-developed as part of a proactive, positive approach to classroom management; and

- consistent routines that include consistent approaches to developing positive relationships across the school and dedicated time for regular community meetings within and beyond classrooms.

These structures are a critical foundation, but what will make them fully successful and bring them fully to life depends on the way in which they are used, modeled, and implemented in practice, as described in greater detail below.

Shared values and norms

Shared values and norms co-developed by students with teachers are part of a proactive, positive classroom management approach that builds community.

Co-developing shared values and norms involves a proactive approach to classroom management as something that is done with students and not to them. School leaders and educators can design environments that are caring and purposeful by including students as active participants in classroom management and conflict resolution, and by organizing classroom structures around communal responsibility, rather than compliance and punishment. (See, for example, Turnaround for Children’s Continuum of Practice on Expectations, Norms and Routines.)

For example, students can be engaged to help create their classrooms’ norms or community agreements—often displayed in a classroom constitution that is posted so that it can be a reminder and a reference point. Students can also take ownership of dozens of activities in the classroom in roles such as materials manager or as a contributor to bulletin boards, classroom activities, or special events. This ensures that all students have voice and membership in the classroom design, norms, and management and allows them to be responsible and contributing members of the community.

Teachers and students together create common agreements for how to behave in various situations, and they discuss and practice how to handle different situations so that students can interact respectfully, take turns, voice their needs and thoughts appropriately, and solve problems that occur. As community members, teachers and peers play an active role in supporting their classmates in learning how to regulate their behavior, and teachers help scaffold children’s development toward self-regulation by providing them with a repertoire of words and strategies to use to manage different situations.

A well-researched example of a developmentally grounded, schoolwide approach to classroom management that involves the co-development of shared norms and values with students is the Consistency Management and Cooperative Discipline approach. (See “The Consistency Management and Cooperative Discipline Approach.”)

For these norms to be fully expressed in the classroom and the school, they should be integrated as part of instruction for students and professional learning for adults, just as any skill is taught. Members of the school community should be able to explain why the norm is important and what it looks like in practice and to offer intentional opportunities to practice and give feedback as to how living out the norm in practice is going. (Learn more about how Valor College Academies does this in “Positive Developmental Relationships.”)

By explicitly teaching the interrelated set of cognitive, social, and emotional competencies that help people cope with their emotions while they learn, develop, and maintain mutually supportive relationships, educators can ensure that students and staff alike have the tools to produce a developmentally healthy environment for the entire community. In the process, adults and students learn to recognize and manage their emotions, access help when they need it, and learn how to solve problems and resolve conflicts together, all of which serves to make schools safer and more nurturing for everyone. (See “Development of Skills, Habits, and Mindsets” for more on supporting the development of these skills.)

Consistent routines

Consistent routines create order, including dedicating time to regular community meetings.

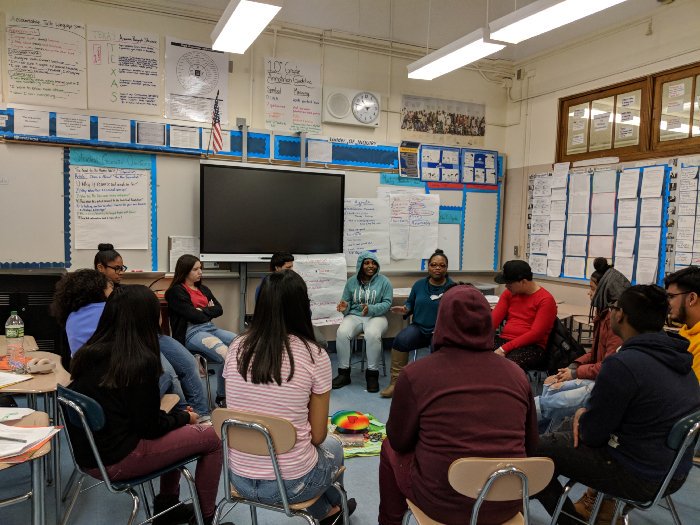

A particularly effective strategy that supports community building is to establish consistent routines by dedicating time in the day for regular community meetings. In elementary schools these may take the form of classroom meetings that start the day or reunite students after lunch or recess. In secondary schools, these meetings may take place as community circles in advisory classes or, periodically, in content classes. Community meetings can help build a caring and collaborative environment in which students have a sense of belonging, voice, and agency over their own learning and behavior. When implemented with intentionality, such meetings offer a respectful setting for students to reflect on, reveal, and problem-solve issues that make them feel vulnerable and to build empathy among peers. Because this setting supports a sense of acceptance and equilibrium, it can contribute to greater engagement in students’ learning and the enactment of interpersonal skills for successful group work in their classes.

At the high school level, Social Justice Humanitas (a public high school in Los Angeles, CA) uses councils as a component of advisory classes to build community and create space for the practice of “listening and speaking from the heart.” During councils, students and teachers sit together in a circle and take turns sharing the positive and difficult things happening in their lives.

Daily classroom-based community meetings can be paired with additional community meetings that bring students and staff together across classrooms or grades. For instance, at Valor Collegiate Academies in Nashville, TN, middle school students and staff participate in weekly meetings, called Valor Circles. Circles are single-gender groupings of about 20 students led by a mentor teacher. Circles incorporate mindfulness exercises and opportunities to share about and work on interpersonal issues. This brief video illustrates the Valor Circles in practice.

Similarly, Harvey Milk Civil Rights Academy, a public elementary school in San Francisco, CA, uses a schoolwide program called “Families.” The Families program builds relational trust and emotional support networks between students and adults to help students feel included in the lunchroom, on the playground, and in school in general. Once a month for an hour on Fridays, students participate in a cross-grade, multifaceted curriculum that includes storytelling, public speaking, and exploration of students’ heritage. Building on the principle that it is important that all students be well known by the adults in the school, Families gives teachers and students alike the opportunity to build relationships with students from every grade level. “It is how they learn to play across the yard,” Principal Sande Leigh said. One teacher added, “I have seen [students] since they were little bitty kid[s].”2 Families gives teachers a chance to get to know students that they did not teach every day, and students get to know a new teacher and students from other grade levels. (See Elementary Schools for Equity for a detailed case study of Harvey Milk Academy and three other elementary schools.)

This learning network includes a group of school districts that are committed to designing more equitable and healing-centered schools and approaches to teaching and learning that center the experiences of Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) students. Guided by the BELE Framework, leaders engage in professional learning and codesign approaches to ensure that youth emerge with strong academic skills, social-emotional wellness, a sense of agency, healthy identity and civic responsibility, and a broader set of competencies that equip them to engage as healthy and happy adults and citizens.

Developing Restorative Practices That Are Trauma-Informed and Healing-Oriented

Systemic approaches that create enabling conditions for safety and belonging include:

- trauma-informed supports and healing practices, including means to learn about students’ experiences and address their needs, as well as strategies such as mindfulness; and

- restorative practices, including community circles, spaces for calming and reflecting, and means for making amends and restoring community.

Trauma-informed supports and practices

Healing and wellness can be promoted by trauma-informed practices that include strong relationships, means to learn about students’ experiences so they can be understood and addressed, and mindfulness to help students center and achieve calm.

Becoming a trauma-informed and healing-oriented school involves providing administrators, educators, and other school personnel with the knowledge and preparation to recognize and respond to those impacted by traumatic stress within the school community and promote wellness for all students. As Joshua Kauffman, a school mental health specialist with Los Angeles Unified School District, describes:

Ultimately, trauma-informed schools understand and recognize that children’s behavior is a developmental response to past experience, so that instead of wondering what’s wrong with a child or immediately beginning to label, we start to ask the question, “What might have happened that explains this child’s behavior?” And all of a sudden, when we do that, understanding can manifest and we can begin to address the underlying needs that the child may have.

The experience of trauma can disrupt the development of neurobiological integration in ways that can affect mood, skill development, learning, emotional well-being, and relational trust. Trauma can be an individual experience that occurs as a function of chronic stressors associated with poverty— such as food or housing insecurity, lack of child care, lack of health care—or any number of other traumatic events, such as illness, loss of a family member, abuse, or bullying. Trauma can also be a collective experience—and may frequently be held in marginalized communities in which families may have to contend with daily challenges of survival; frequent incidents of discrimination; or violence associated with gangs, police shootings, or other causes.

The experience of trauma can cause students to become withdrawn, angry, disruptive, inattentive, or unable to focus. They may lose confidence in themselves and in the ability of those around them to handle their needs. They may be unable to complete classwork or homework and may have less capacity to handle other stressors calmly, losing composure at seemingly small events or challenges.

While it is important to acknowledge the impact of trauma on learning, it is critical that administrators, teachers, and school personnel also implement practices that center healing on both an individual and collective level.

One framework for trauma-informed school practice identifies the following four characteristics:

- Attachment-focused: Educators engage in attunement, mentoring, and a consistent ethic of care to allow students to feel safe and cared for. This promotes neural integration, which is the key to resuming healthy development and achieving success in the academic environment. Efforts within attachment-focused learning communities are more likely to be healing, allowing students to increase resilience.

- Neurobiology-informed: Trauma-informed practitioners rely on their understanding of the neurobiology of development, stress, and trauma. This knowledge base makes it clear that students struggling in the school setting may be experiencing stressors that are school based as well as caused by out-of-school factors. Significant stress and trauma are caused by implicit and explicit social values related to aspects of social identities that are either privileged or marginalized, such as race, class, language background, dis/ability status, sexual orientation, and more. Our understanding of stress and the brain requires educators to continually re-examine existing school practices to change those that may exacerbate trauma. As described in this section, these can include disciplinary practices, grouping and tracking practices, and other sources of stigma.

- Strengths-based: A strengths-based trauma-informed approach looks for the capacities students have developed and acknowledges the ways in which they—and often their family members—are seeking to engage, adapt, and develop resilience to adverse circumstances. Insight into broader system factors reminds trauma-informed educators not to blame caretakers, but to view each other as partners in problem-solving and healing.

- Community-driven: Trauma-informed practice is ultimately a commitment to being in community in a manner that provides a welcome and inclusive environment fostering relational safety and well-being, the basic ingredients we all need to thrive throughout our lives. A consistent ethic of care means that the relational values educators extend to students are offered to each other as well. Caring about educator well-being is a central value, since attuned and supportive interpersonal relationships nurture their resilience and well-being, which is necessary for them to attend to student well-being.3

Importantly, school designs that are trauma- and healing-informed include structures and practices to support attachment and recognize strengths and needs by ensuring that every student is known and supported by adults who have opportunities to learn about their lives and experiences so that they can marshal assistance when needed. These include structures such as advisories, looping, and smaller learning communities. (See “Positive Developmental Relationships” for more on attachment-building structures and practices.)

For students coping with trauma or emotional challenges, schools can:

- Train educators and staff to recognize students who are experiencing trauma in their lives and respond to them with caring instead of frustration or punishment.

- Increase access to school counseling—one-on-one and in small groups for students dealing with similar kinds of trauma—as well as to a broader system of supports. (See “Integrated Support Systems” for more detail on designing and implementing school support systems.)

- Increase outreach to families to gather information, support parents, and co-create collaborative approaches to support student health.

- Create quiet spaces in classrooms or in the building for cooling down or restorative time where students can defuse and reflect, followed by opportunities for conversation.

For instance, as part of an integrated approach to promoting social and emotional learning, teachers at Lakewood Elementary School in Sunnyvale, CA, use the “Chillax Corner” strategy. The Chillax Corner offers space and activities for students to regulate their emotions when they are upset. It is a quiet area in the classroom with a table, a chair, and objects such as stress balls and fidget spinners that students can use to relax and prepare to participate in classroom activities. The Chillax Corner is introduced at the beginning of the school year and remains an important space in the classroom throughout the year where students can consistently go as they recognize the need for space and time to reflect and regulate their emotions. (See Preparing Teachers to Support Social and Emotional Learning: A Case Study of San Jose State University and Lakewood Elementary School for a closer look at these practices in action.)

Trauma-informed and healing-oriented schools implement practices that promote wellness for all students in addition to targeted supports for students dealing with trauma and other challenges. There is a range of strategies that schools can implement to reduce stress and promote physical and emotional well-being for all students. These include mindfulness and breathing practices used as a part of community meetings or lessons; breaks throughout the day that offer physical movement opportunities, such as active games, dance, yoga, martial arts, and exercise; lessons on brain science, growth mindset, stress, and healthy lifestyles in the core of elementary curriculum and secondary science and health curriculum; and classroom environments in which acknowledgment of stress and emotional issues in students’ lives—shared and addressed appropriately—is simply part of the classroom culture. (See this brief video, Getting Started With Trauma-Informed Practices.)

Mindfulness is a particularly promising practice to consider. The use of mindfulness strategies and other techniques for calming oneself, as well as for monitoring and redirecting attention, has been found to benefit brain architecture, learning, attention, and stress management. Mindfulness practice—which focuses attention on breathing and cultivates greater awareness of one’s experience infused with attention to care and compassion—and related contemplative practices have been linked to greater social and emotional competencies, including capacities for regulation, as well as reductions in stress and implicit bias.

For example, at Codman Academy, a public k–12 school in Boston, MA, teachers do a short, guided mindfulness practice when students return from the dining hall after lunch to transition from the energy of lunch and recenter themselves for learning. As one 2nd-grade student describes, “We do mindfulness because during lunch it gets a little crazy. So, when we go upstairs, we calm down so we can transfer to writing.”4 This brief video shows mindfulness in practice in one of the 2nd-grade classrooms and illustrates how one teacher accommodates students’ different needs by offering choices in how they engage in the mindfulness practice.

Mindfulness strategies can also be integrated into instruction and can be designed to include both educators and school staff, which supports their self-care and stress management abilities. Pure Edge provides several free mindfulness tools that have been adopted by some districts—such as Jackson, MS, and Philadelphia, PA—and by entire states, including Delaware and Rhode Island.

Restorative practices

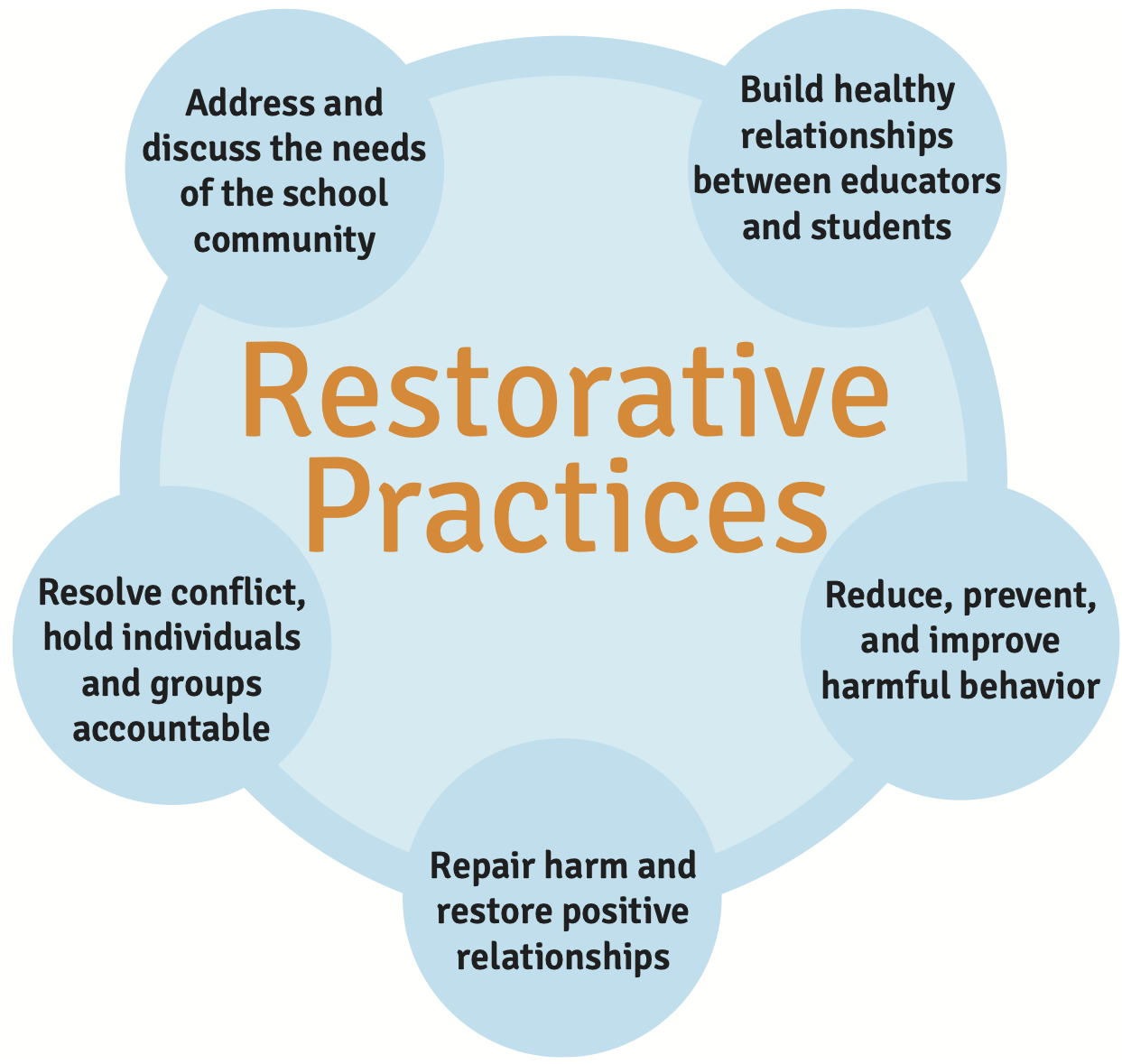

Restorative practices that increase safety and promote stronger academic, social, and emotional outcomes include community circles, strategies for conflict resolution, and means for making amends and restoring community.

Because efforts to support students’ well-being and optimal development cannot enable meaningful long-term growth for students in environments that are otherwise authoritarian, punitive, and exclusionary, in order to create a healing-oriented environment, schools need to be able to eliminate zero-tolerance policies and exclusionary discipline and focus on educative and restorative practices.

Zero-tolerance policies that were widespread in many states and districts have led to high rates of suspension and expulsion that have also proved to be discriminatory, with students of color and students with disabilities disproportionately excluded from school. Evidence shows that this is, by and large, not because of worse behavior but because of harsher treatments for minor offenses, such as tardiness, talking in class, and other nonviolent behavior.

Restorative practices enable educators and school leaders to understand how they may unintentionally trigger or escalate problem behavior; these practices help students and staff cultivate strategies for resolving conflict and creating healthier, more positive interactions.5 As Tiana Lee, the Alternatives to Suspensions Specialist at Brooklyn Center High School in Brooklyn, MN, described:

The impacts of suspensions were clear: Our neediest students were falling further behind, and excluding them did little to improve their behavior. But simply ending suspensions was not enough, as we had still not begun to address the root causes of students’ misbehavior.

Central to a restorative justice approach is the belief that all people have worth and that it is important to build, maintain, and repair relationships within a community.6 Restorative practices enable adults and students to resolve conflicts and to sustain relationships, contributing to the overarching goal of creating a supportive school environment. Restorative practices are also essential to a trauma-informed approach that promotes healing among students and other members of the school community.

Restorative practices are “processes that proactively build healthy relationships and a sense of community to prevent and address conflict and wrongdoing.”7 (See Figure 3.1.) Relationships and trust are supported through universal interventions such as daily classroom meetings, community- building circles, and conflict resolution strategies, which are also part of many social and emotional learning programs. (See “Development of Skills, Habits, and Mindsets” for more on these practices.) These strategies are supplemented with restorative conferences, often managed through mediation by trained staff or peers, when a challenging event has occurred.

In addition to explicit conflict resolution training for students and staff, a restorative justice approach deals with conflict through systems that allow students to reflect on any mistakes, repair damage to the community, and get counseling when needed. Creating an environment in which students learn to be responsible and are given the opportunity for agency and contribution can transform social, emotional, and academic behavior and outcomes.

What Are Restorative Practices?

Accumulating research evidence suggests that shifting to restorative practices, with robust supports to enable the adults in schools to do so, reduces the use of exclusionary discipline, resulting in fewer and less racially disparate suspensions and expulsions while also making schools safer, improving school climate and teacher–student relationships, and improving academic achievement.8

The more comprehensive and well infused the restorative justice approach is within the school culture and ethos, the stronger the outcomes.9 For example, a continuum model including proactive restorative exchanges, affirmative statements, informal conferences, large group circles, and restorative conferences substantially changed school culture and outcomes rapidly in one major district, as disparities in school discipline were reduced every year for each racial group, and gains were made in academic achievement across all subjects in nearly every grade level.10

Schools that are working toward infusing restorative practices aim to create an environment that is respectful, inclusive, and supportive. Research indicates that a key strategy to fostering such a culture is to proactively nurture relationships characterized by active listening and respect among students and staff.

These restorative practices can be implemented at all grade levels. Earlier in this section, we shared the use of daily dialogue circles at Glenview Elementary School in Oakland, CA, one of the schools implementing schoolwide restorative justice practices, to check in, settle disputes, teach skills, and build community (illustrated in this video). Another approach to building these skills is shown in this Bronxdale High School vignette.

The Model Code toolkit is organized into five chapters: (1) Education; (2) Participation; (3) Dignity; (4) Freedom From Discrimination; and (5) Data, Monitoring, and Accountability. Each of these chapters addresses a key component of providing a quality education and reflects core human rights principles and values. Each chapter includes recommended policies for states, districts, and schools.

This guide was designed to support someone facilitating restorative practices in their school to create an implementation plan for introducing restorative practices to the school community.

Fostering Inclusive, Culturally Responsive Learning Environments

In addition to creating consistent, caring learning environments, it takes a set of proactive efforts to ensure that these environments are inclusive for all students and are culturally responsive and affirming. Structures that can create incentives for such efforts include culturally responsive and affirming curriculum materials and activities used in heterogeneous classrooms that provide universal access to high-quality curriculum, along with socially inclusive and supportive extracurriculars. Within these structures, practices that affirm students’ value, draw on their cultural resources, and dismantle stereotype threats are critically important.

Inclusive and culturally responsive learning environments

“[The teachers] treat us like people with emotions. You have real relationships with your teachers. We want to do our work because we care about our teachers.”

Inclusive and culturally responsible learning environments affirm students’ value by acknowledging their learning, contributions, and capacity.

It is often said that students learn as much for a teacher as from a teacher. And the teachers they learn the most from are those they believe care about them and see them as worthy of their investment. At Bronxdale High School, staff have developed explicit practices to ensure that they communicate the many ways they value each of their students, including the “Affirmation Station” shown in Figure 3.2.

Affirmation Station at Bronxdale High School

As they are reinforcing a positive learning environment, teachers can affirm their students’ interpersonal and problem-solving skills, even as they are helping them acquire more skills. The story in “Creating an Affirming and Emotionally Safe Learning Environment” shows how a teacher at San Francisco Community School helps her 4th- and 5th-grade students feel affirmed as she creates a safe learning environment where students can take risks, develop confidence, and grow emotionally and academically.

Directly addressing stereotype threats and creating identity-safe, culturally affirming environments improve academic performance while also strengthening belonging and a growth mindset.

At the start of this section, we described how learning is undermined when children experience a sense of threat. A particularly salient threat in our society and education systems is social identity threat, which can be triggered whenever a member of a group that is stigmatized in society feels they are at risk of being mistreated or misperceived in a given situation.12 Both inside and outside of school, students often receive messages that they are less valued or less capable as a function of their race, ethnicity, family income, language background, immigration status, dis/ability status, gender, sexual orientation, or other status. When those views are reinforced and internalized, they can become self-fulfilling prophecies. Stereotype threat, “a type of social identity threat that occurs when one fears being judged in terms of a group-based stereotype,”13 has been found to induce the body’s stress response, leading to impaired performance on school tasks and tests that does not reflect students’ actual capacity.

When adults appreciate and understand students’ individual experiences, assets, needs, and backgrounds, they are able to support their students in ways that counteract societal stereotypes that may undermine their confidence. Such knowledge of students and respect for their backgrounds and the societal stressors on students can help teachers design instruction in ways that build their confidence and interrupt the negative effects of discrimination.

One aspect of this work is the use of multimodal teaching strategies that deliberately support success for students who learn in different ways—like those that are part of Universal Design for Learning. (See “Rich Learning Experiences and Knowledge Development” for more discussion of these strategies.) Considered essential for students with disabilities, these strategies help a wide range of learners experience success in the classroom. In addition, teachers can help affirm students by finding ways to ensure that they are able to engage in classroom activities. For example, a teacher may monitor patterns of classroom engagement and connect with those who may not actively speak up to find out how to support their participation in ways that they feel safe.

Educators can also use values affirmation interventions that guide students to reflect on and write about things most important to them—such as their relationships with friends or family, their personal interests, their personal goals for learning—during critical times during the year: the beginning of the school year, prior to tests, and before big holiday seasons or breaks. These interventions tell students that teachers want to learn about them. They also provide teachers with important information about students that enriches teachers’ ability to draw on student experiences and goals in the ways they make connections in the classroom. Multiple studies have found that such strategies reduce the effect of stereotype threat among middle school students, resulting in higher academic performance for Black students for as long as 2 years after the interventions.14

In identity-safe and affirming classrooms, teachers avoid labeling students in ways that implicitly categorize some as worthy and others as unseen or problematic, and they instead find many ways to provide positive affirmations about individual and group competence. Support for cultural pluralism that builds on students’ experiences and intentionally brings students’ voices and experiences into the classroom also helps create an identity-safe and engaging atmosphere for learning to take place and enables all students to have a sense of safety and belonging.

Teachers can also center projects around community engagement in ways that are culturally sustaining and affirming. (See “Connecting to the Community Through the Arts.”) They may also choose and make available readings that portray different cultural experiences and foster culturally affirming learning opportunities. The Historically Responsive Literacy Framework is a tool that aids teachers in this approach.

Culturally responsive and affirming environments create the conditions for productive learning that require struggle with challenging academic content because students feel they are expected and supported to succeed.

Heterogeneous, supportive learning environments

Stronger outcomes for students are achieved through universal access to high-quality curriculum and extracurricular activities in supportive, heterogeneous learning environments.

To create a school environment that is inclusive and explicitly anti-racist, schools must identify and eliminate harmful practices that can create stigma, exacerbate stress, and hinder the development of skills and mindsets for learning. This includes practices that perpetuate negative stereotypes, bullying, or microaggressions, including punitive and unfair discipline practices. It also includes practices that segregate or shame students—such as separate lunch lines for those receiving free or reduced-price lunch; identification or shaming of students who cannot pay school fees; listing students’ grades or test scores publicly; or writing names on the board to identify students for punishment if they have violated a rule, rather than engaging in restorative practices.

Finally, exclusionary practices that can communicate differential worth and undermine achievement include tracking mechanisms that exclude students from high-quality curriculum.

Decades of research show that tracking harms students by reducing achievement for those exposed to a low-level curriculum. If two students who are achieving at the same level at the start of a school year are differently tracked, evidence shows that the one tracked “up” will have higher achievement at the end of the year than the one tracked “down.” Their achievement is a function of the curriculum they have experienced, not their perceived ability at a moment in time. Low- tracked classes generally create experiences of both low-level, unengaging content and stigma. Less-experienced and less-expert teachers are also typically assigned to low-tracked classes.18 Despite evidence of the benefits of detracking, in practice, tracking remains widespread in American schools, from the segregation of “gifted and talented classes” as early as kindergarten to the creation of tracks, lanes, or streams in middle school and high school for students perceived to be following different paths to their futures.19

Many new schools have been developed over the past three decades that have eschewed tracking, and a number of them are highlighted in this volume. Established schools have also successfully moved forward with detracking, as illustrated by Hillsdale High School’s three-year conversion process from a large, traditional public school into three small learning communities with heterogeneous grouping in 9th and 10th grades, before students begin to specialize around their interests. (Learn more about Hillsdale’s redesign process and that of other public high schools that have done the same in the Windows on Conversions case study series.)

High-quality learning experiences can also be provided through extracurricular activities if engaging opportunities are made available without screens or financial barriers. There is strong evidence that suggests that participating in socially supportive extracurriculars can affirm students’ identities; strengthen their interpersonal skills for forming healthy relationships; and, in some cases, provide them with important future career skills and credentials.20

Although almost every school offers extracurricular activities, such as music, academic clubs, and sports, there are certain types of extracurriculars that are less likely to be available to many students, either because they are selective (e.g., require auditions and/or restrict participation to just a few students) or because they require financial commitments or other resources for uniforms, equipment, transportation, and the like.21 Nonacademic clubs, such as affinity groups, vocational or professional clubs, and service or hobby clubs, have been found to be less available in less affluent schools but may in fact be more socially supportive for a wider variety of students. Offering high- status extracurricular opportunities and ensuring that there are no barriers to participation can change students’ lives, as the Social-Impact Robotics Club at East Palo Alto Academy shows.

Summary

In environments that are consistently caring, safe, attuned to relationships, inclusive, and culturally responsive, youth learning and well-being will be not only promoted, but empowered. There is no one formula for creating and sustaining these environments, but key structures—including co-developed norms, restorative approaches to discipline, heterogeneous classrooms and socially supportive extracurriculars, and culturally affirming learning opportunities—can increase equity of experience, opportunity, and outcomes for all students.

Where to Go for More Resources

This learning network includes a group of school districts that are committed to designing more equitable and healing-centered schools and approaches to teaching and learning that center the experiences of Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) students. Guided by the BELE Framework, leaders engage in professional learning and codesign approaches to ensure that youth emerge with strong academic skills, social-emotional wellness, a sense of agency, healthy identity and civic responsibility, and a broader set of competencies that equip them to engage as healthy and happy adults and citizens.

The Model Code toolkit is organized into five chapters: (1) Education; (2) Participation; (3) Dignity; (4) Freedom From Discrimination; and (5) Data, Monitoring, and Accountability. Each of these chapters addresses a key component of providing a quality education and reflects core human rights principles and values. Each chapter includes recommended policies for states, districts, and schools.

This guide was designed to support someone facilitating restorative practices in their school to create an implementation plan for introducing restorative practices to the school community.

Endnotes

- Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2014). Student-centered learning: Impact Academy of Arts and Technology. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education. https://core.ac.uk/download/71364837.pdf.

- Wentworth, L., Kessler, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2013). Elementary schools for equity: Policies and practices that help close the opportunity gap. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education. https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/elementary-schools-equity-policies-and-practices-help-close-opportunity-gap.pdf.

- Berardi, A. A., & Morton, B. M. (2019). Trauma-Informed School Practices. George Fox University. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=pennington_epress.

- Edutopia. (2019). Getting ready to learn with mindfulness [Video]. https://www.edutopia.org/video/getting-ready-learn-mindfulness.

- Losen, D. J. (2015). Closing the Discipline Gap: Equitable Remedies for Excessive Exclusion. Teachers College Press.

- Evans, K., & Vaanering, D. (2016). The Little Book of Restorative Justice in Education: Fostering Responsibility, Healing, and Hope in Schools. Good Book.

- Schott Foundation, Advancement Project, American Federation of Teachers, & National Education Association. (2014). Restorative practices: Fostering healthy relationships and promoting positive discipline in schools. http://schottfoundation.org/sites/default/files/restorative-practices-guide.pdf.

- Augustine, C. H., Engberg, J., Grimm, G. E., Lee, E., Wang, E. L., Christianson, K., & Joseph, A. A. (2018). Can restorative practices improve school climate and curb suspensions? An evaluation of the impact of restorative practices in a mid-sized urban school district. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2840.html; Fronius, T., Darling-Hammond, S., Sutherland, H., Guckenburg, S., Hurley, N., & Petrosino, A. (2019). Restorative justice in U.S. schools: An updated research review. WestEd. https://www.wested.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/resource-restorative-justice-in-u-s-schools-an-updated-research-review.pdf; Gregory, A., Clawson, K., Davis, A., & Gerewitz, J. (2016). The promise of restorative practices to transform teacher–student relationships and achieve equity in school discipline. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 26(4), 325–353.

- Fronius, T., Darling-Hammond, S., Sutherland, H., Guckenburg, S., Hurley, N., & Petrosino, A. (2019). Restorative justice in U.S. schools: An updated research review. WestEd. https://www.wested.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/resource-restorative-justice-in-u-s-schools-an-updated-research-review.pdf.

- Gonzalez, T. (2015). “Socializing Schools: Addressing Racial Disparities in Discipline Through Restorative Justice” in Losen, D. J. (Ed.). Closing the Discipline Gap: Equitable Remedies for Excessive Exclusion (pp. 151–165). Teachers College Press.

- Friedlaender, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2007). High schools for equity: Policy supports for student learning in communities of color. The School Redesign Network at Stanford University. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/media/4276/download?inline&file=High_Schools_for_Equity_SCOPE_REPORT.pdf.

- Major, B., & Schmader, T. (2018). “Stigma, Social Identity Threat, and Health” in Major, B., Dovidio, J. F., & Link, B. G. (Eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health (pp. 85–104). Oxford University Press.

- Murphy, M. C., Steele, C. M., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Signaling threat: How situational cues affect women in math, science, and engineering settings. Psychological Science, 18(10), 879–885.

- Cohen, G. L., Garcia, J., Purdie-Vaughns, V., Apfel, N., & Brzustoski, P. (2009). Recursive processes in self-affirmation: Intervening to close the minority achievement gap. Science, 324(5925), 400–403. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1170769.

- Ancess, J., & Rogers, B. (2015). Social emotional learning and social justice learning at El Puente Academy for Peace and Justice. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/2024-04/SEL_Three_High_Schools_El_Puente_SCOPE_CASESTUDY.pdf.

- de Almeida, A. J. (2003). El Puente Academy for Peace and Justice Integrated Arts Project Handbook. El Puente Academy for Peace and Justice, p. 3.

- de Almeida, A. J. (2003). El Puente Academy for Peace and Justice Integrated Arts Project Handbook. El Puente Academy for Peace and Justice, p. 2.

- Oakes, J. (2005). Keeping Track: How Schools Structure Inequality. Yale University Press; Rubin, B. (2006). Tracking and detracking: Debates, evidence, and best practices for a heterogeneous world. Theory Into Practice, 45(1), 4–14.

- Oakes, J. (2005). Keeping Track: How Schools Structure Inequality. Yale University Press.

- Barber, B., Stone, M. R., Hunt, J. E., & Eccles, J. S. (2005). “Benefits of Activity Participation: The Roles of Identity Affirmation and Peer Group Norm Sharing” in Mahoney, J. L., Larson, R. W., & Eccles, J. S. (Eds.). Organized Activities as Contexts of Development: Extracurricular Activities, After-School and Community Programs (pp. 185–210). Psychology Press.

- O’Brien, E., & Rollefson, M. (1995). Extracurricular participation and student engagement. National Center for Education Statistics Policy Issues, 95(741), 1–4.

References

For more information on the research supporting the science and pedagogical practices discussed in this section, please see these foundational articles and reports:

- Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context. Applied Developmental Science, 23(4), 307–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1398649(link is external).

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B. J., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791(link is external).

- Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(1), 6–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1398650(link is external).