Integrating Design Principles in Schools

Overview

Today we have a tremendous opportunity to reimagine our education system by using what we know from the science of learning and development. Infusing school environments and practice with this knowledge can ensure far better learning experiences and opportunity for students— experiences that are transformative, empowering, personalized, and culturally affirming. In addition, it can support practitioners in identifying and stopping practices that inhibit students’ learning, especially students from marginalized groups who—because of their race, ethnicity, income, language background, dis/ability status, sexual orientation, or other social identity—have often been exposed to ineffective and discriminatory practices that inhibit their full development.

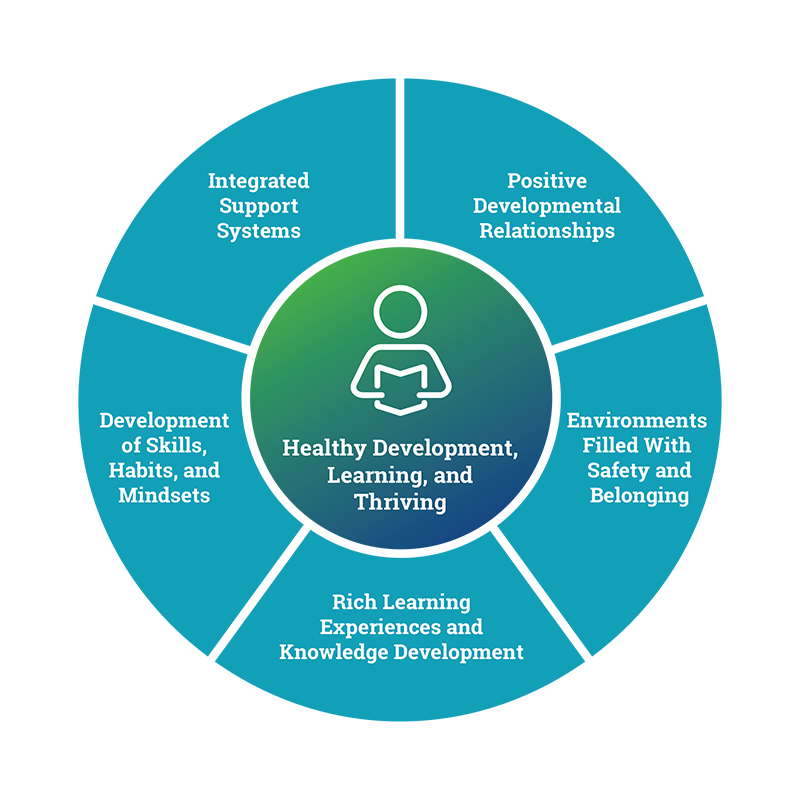

Developmental and learning science provides us with optimism about what all young people are capable of. The contexts and relationships they are exposed to influence what they learn and who they become. Today, we can use the Guiding Principles for Equitable Whole Child Design and its associated design principles to build environments in all of our classrooms, schools, and community learning settings that enable children to develop and thrive. (See Figure 7.1.) By designing schools that integrate the five elements—Positive Developmental Relationships; Environments Filled With Safety and Belonging; Rich Learning Experiences and Knowledge Development; Development of Skills, Habits, and Mindsets; and Integrated Support Systems—we can help youth build resilience and knowledge; develop their full selves; and grow skills, habits, and mindsets they need to live lives of fulfillment. While the Guiding Principles for Equitable Whole Child Design are each critical to supporting youth learning and development, their impact is deeply felt and effective when practitioners integrate all five into a coherent, continuously reinforcing set of practices.

What the Science Says

The human brain is a dynamic, integrated living system that operates in coordination with other systems. The tissue it is made up of is the most susceptible to change from experience than any other tissue in the human body. Complex skills, whether riding a bike, developing resilience, or learning to read, reflect the integrating properties of our continually developing brains and bodies. Emotional well-being and social competence provide a strong foundation for emerging cognitive abilities, and together they form the bricks and mortar of healthy brain architecture. The human brain grows by integrating all other systems—including those that govern feeling, thinking, acting, cognition, and processing—in ways that are highly sensitive to the physical and sociocultural context of a person’s life.

Figure 7.1

Guiding Principles for Equitable Whole Child Design

The three core principles of human development are: (1) the astounding malleability of the human brain and body, (2) the fact that growth depends on experience, and (3) the importance of contexts in shaping development. Throughout life experiences, relationships and environments activate neural pathways, generating electrical activity that continuously strengthens the connections between brain structures and creates new ones. This is what is meant by the “wiring” of the brain, or the integration of the brain. Beginning early in life, more than 1 million connections form between brain structures per second.1 And the way these connections form matters for what the brain can do. As Hebb’s Law states, “Neurons that fire together, wire together.”2 It is these developing circuits that enable the emergence of increasingly complex thoughts, skills, knowledge, learning, and behavior; the expression of our identities, our interests, and our passions; and ultimately the expression of our potential. This is what is meant by the integration of the brain.

Once we understand that environments, experiences, and relationships drive the wiring of our brains, the task and responsibility before us becomes clear: to design settings and experiences for optimal development and learning. This is the purpose and the foundation for the Guiding Principles for Equitable Whole Child Design presented in this playbook. The development of a whole child emerges when we combine the five elements into experiences that connect to one another.

The driving force in development is the movement from simple to complex—through the agency of the child who plays an active role in developing skills. Skills and knowledge do not emerge fully formed but are built through practice—something we see every time we learn a new skill, such as reading, playing a musical instrument, and learning a sport. This process also means that the young person’s agency in building new skills will be based on what they are encouraged to do and the resources and supports available to them. Like a web with many strands, there are different possible pathways in the development of complex skills, and these skills are interdependent, with more complex capabilities emerging as earlier ones are internalized and specific supports become available.

Supporting the learning of a complex skill means that even the most discrete skill, like solving an algebra word problem, needs to take into account the whole person learning that skill: their prior experience, culture, history, foundational skill development (in reading and math), identity (and identity threat), agency, and motivation. Young people are the sum of all these dimensions. If educators teach only to the discrete math skills, some children may learn the skills or content. But if they teach to the whole child, they can support all students in understanding the content and skills being taught, becoming curious to learn more, and being able to apply them to other problems.

What Does an Integrated Whole Child Approach Look Like in Schools?

Given what we know about the interconnectedness of the brain and development, it is important for practitioners to design learning settings that enable young people to develop their whole selves in the learning process. There is not just one way to integrate whole child practices and structures in a school or community learning setting. Rather, there are a number of ways that educators can nurture students’ assets and address their needs and challenges to create equitable and impactful school settings. The case of the Springfield Renaissance School, a school that serves students in grades 6 through 12 in Springfield, MA, is one illustration of integrated practice, and the San Francisco Community School, serving students in grades kindergarten through 8, is another.

Practitioners at San Francisco (S.F.) Community School have also designed their school in line with the science of learning and development, implementing a unique set of whole child structures and practices that meet the needs of their learners and communities. S.F. Community School is a public k–8 school in San Francisco, CA, that seeks to include English learners and students with disabilities, and the majority of students served by the school are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. Educators at the site engage youth in hands-on, student-centered learning experiences with ample scaffolds. This learning, which builds students’ knowledge and develops valued skills, habits, and mindsets, is bolstered by structures that allow relationships to flourish, collaboration to ensue, and supports to be identified.

Barriers and Solutions to Taking Whole Child Design to Scale

Science and research provide us with guidance on how to create more powerful school communities that provide better learning experiences and opportunities for all students, which are transformative, empowering, and culturally affirming. Despite this growing knowledge around how to create powerful learning environments, it remains challenging for districts and schools to create and sustain learning settings that integrate elements of equitable whole child design.

Progress has been impeded by both historical traditions and current policy built on dated assumptions about school design, accountability, assessment, and the nature of teaching and learning. While most industries look very different from how they looked a century ago—think medicine, aviation, and publishing, for example—our education system remains seemingly stuck in another time, reflecting the designs created in the early 20th century to accommodate mass education using assembly-line technologies. Our youth are entering a totally new world—one in which knowledge is rapidly expanding; technology will take over most low-skilled work; and most jobs will require high levels of knowledge, skill, and capacity to constantly learn and apply new ideas to uncharted problems. Yet our education system is still structured to prepare a small minority of students for college and creative careers, and the rest—particularly students of color and students from low-income families—for factory jobs that no longer exist.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a disruption of the status quo and presents an opportunity to seize this moment for change. District and school leaders can harness this unprecedented time—as school is necessarily being reconceptualized to educate stakeholders on the science summarized here—and begin phasing in structures and practices to create supportive and powerful learning environments, both virtual and in person.

What can we do to create more schools that teach all students the complex skills they actually need for academic and life success while affirming their identities and potential, developing their character, and fostering equity? Evidence suggests that we must:

- redesign schools to support high-quality teaching and strong relationships;

- rethink curriculum, assessment, and accountability structures so that they focus on powerful learning with associated supports;

- improve professional learning opportunities;

- build unified integrated support systems; and

- take a systemic approach that enables change in all schools.

Conclusion

Education has long been central to the promise of the United States and its democracy. However, our current education system has not been designed to promote the equitable opportunities or outcomes that today’s children and families deserve and that our democracy and society need. Our system was designed for a different world—to support mass education preparing students for their presumed places in life. That world believed that talent and skills were scarce; it trusted averages as a measure of individuals; and it was a world in which racist beliefs and stereotypes shaped the system so that only some children were deemed worthy of opportunity.

To achieve the transformation we need today, education systems must be willing to embrace what we know about how children learn and develop. The core message from science is clear: The range of students’ academic skills and knowledge—and, ultimately, students’ potential as human beings—can be significantly influenced through exposure to learning environments that use whole child design. To create this transformation, the science, structures, and practices highlighted in this playbook can become the foundation for a new approach to learning when integrated and implemented—one that supports equity for all students and the development of the full set of skills, competencies, and mindsets that young people need to live and thrive in their diverse communities.

Where to Go for More Resources

The BELE Network works with educators, policymakers, school support organizations, and other stakeholders to create equitable learning environments that are grounded in the science of learning and development. Guided by its transformation framework, the network aims to create resources and tools that support practitioners and decision-makers in transformational change. In addition, the BELE Network supports and convenes partners to share learnings from this equity-oriented change process and to elevate the ways that the field can make equitable learning environments a sustainable reality.

City Connects partners with schools to transform existing student supports in a school and in the surrounding community into an integrated support system of care that addresses the strengths and needs of each student across all developmental domains. To date, City Connects has implemented its approach in 82 schools across six states, helping them to create and execute a tailored plan of resources, opportunities, and relationships, with the goal of supporting each student to be ready to learn and engage in school.

The Coalition for Community Schools is an alliance of national, state, and local organizations in k–12 education, youth development, community planning and development, family support, health and human services, government, and philanthropy. It offers a range of tools and resources that can help educational leaders to build and sustain community school models and initiatives in their area, including opportunities to connect with technical assistance providers that can help communities improve their planning and management.

The CORE Districts are a collective of districts across California that collaborate to build educator capacity and effective data processes that support whole child education. Since 2013, they have established a shared data system that incorporates academic and nonacademic indicators and have facilitated interdistrict professional learning that supports schools and systems in their areas of strength and struggle. Through their collective work, the CORE Districts have shared the key lessons and takeaways that have emerged in their efforts to support continuous improvement within and across districts and schools, and with state and federal policymakers.

A number of schools have been effective at rejecting the factory model and redesigning their systems to create safe environments with opportunities for exciting and rigorous academic work. Their successes have ideas in common, offering 10 important lessons for other schools. This report offers a powerful evidence-based blueprint to create learning environments that are more humane, enriching, and productive than our current models.

Marshall Street at Summit Public Schools is a coalition of educators working to systematically improve opportunities for students across the country. As part of their efforts, Marshall Street has curated a resource library, which contains papers, toolkits, and frameworks for educators and school leaders to increase opportunities for students. These include “Clearing the Path: How Schools Can Improve College Access and Persistence for Every Student” and “Designing Aligned School Models: A Framework for School Improvement,” which outline concrete steps for designing school models that support student success.

Turnaround for Children works to support practitioners in advancing and implementing whole child educational practices. To this end, the organization produces research-based tools for educators, such as a toolkit on how to use a whole child vision to assess and plan for tiered systems of support and resources to accelerate healthy student development and achievement. In addition, Turnaround for Children works with schools, districts, and networks across the country, which, to date, includes training, coaching, and support to over 220 school leaders in 76 schools to help create healthy learning environments that catalyze success and well-being.

Endnotes

- Center on the Developing Child. (2007). InBrief: The science of early childhood development. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/inbrief-science-of-ecd/.

- Hebb, D. (1949). The Organization of Behavior. A Neuropsychological Theory. Wiley.

- Callahan, R. E. (1962). Education and the Cult of Efficiency. University of Chicago Press; Tyack, D. B. (1974). The One Best System: A History of American Urban Education. Harvard University Press.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Bae, S., Cook-Harvey, C. M., Lam, L., Mercer, C., Podolsky, A., & Leisy Stosich, E. (2016). Pathways to new accountability through the Every Student Succeeds Act. Learning Policy Institute. http://learningpolicyinstitute.org/our-work/publications-resources/pathways-new-accountability-every-student-succeeds-act.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Oakes, J., Wojcikiewicz, S., Hyler, M. E., Guha, R., Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Cook-Harvey, C., Mercer, C., & Harrell A. (2019). Preparing Teachers for Deeper Learning. Harvard Education Press.

- Adelman, H. S., & Taylor, L. (2018). Transforming Student and Learning Supports: Developing a Unified, Comprehensive, and Equitable System. Cognella.

- Adelman, H. S., & Taylor, L. (2018). Improving school improvement. Center for MH in Schools & Student/ Learning Supports at UCLA. http://smhp.psych.ucla.edu/pdfdocs/improve.pdf; Adelman, H. S., & Taylor, L. (2017). Addressing barriers to learning: In the classroom and schoolwide. Center for MH in Schools & Student/Learning Supports at UCLA. http://smhp.psych.ucla.edu/pdfdocs/barriersbook.pdf.

- Adelman, H. S., & Taylor, L. (2018). Transforming Student and Learning Supports: Developing a Unified, Comprehensive, and Equitable System. Cognella.

- Ancess, J., Rogers, B., Duncan Grand, D., & Darling- Hammond, L. (2019). Teaching the way students learn best: Lessons from Bronxdale High School. Learning Policy Institute; Hernández, L. E., Darling-Hammond, L., Adams, J., & Bradley, K. (with Duncan Grand, D., Roc, M., & Ross, P.). (2019). Deeper learning networks: Taking student-centered learning and equity to scale. Learning Policy Institute.

References

For more information on the research supporting the science and pedagogical practices discussed in this section, please see these foundational articles and reports:

- Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context. Applied Developmental Science, 23(4), 307–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1398649(link is external).

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B. J., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791(link is external).

- Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(1), 6–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1398650(link is external).